Cross-Cutting Report No. 2: Women, Peace and Security

Introduction • Historical Context • Women, Peace and Security: the Normative Framework • Resolutions • Presidential Statements • Mission Mandates • Timor-Leste Case Study • Secretary-General’s Reports on Country Situations • Security Council Visiting Missions • Security Council Engagement with Stakeholders • International Legal Framework • Addressing Violations • DRC Case Study • Council Dynamics • How Successful has the Security Council Been • The 2010 Anniversary and Related Events

1. Introduction

There is now very wide acceptance of the fact that modern armed conflict has a disproportionate impact on women and girls even though most are not directly engaged in combat. The significance of Security Council resolution 1325–adopted in October 2000–lies in the way it links the impact of war and conflict on women on the one hand and also promotes their participation in various peace and security processes such as in peace negotiations, constitutional and electoral reforms and reconstruction and reintegration on the other.

The Council’s decision to take up women, peace and security as a separate thematic topic flowed out of the Council’s broader thematic agenda. In the twelve months prior to resolution 1325, the Council had adopted its first resolutions on protection of civilians and children and armed conflict. This thematic examination was taking place after a bloody decade of peacekeeping failures, such as in Somalia, Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia. As part of the examination of the broader atrocities committed, it became clear that, in Rwanda and Bosnia in particular, significant attacks had occurred specifically targeting women, including reports of systematic sexual violence.

Concerned about this pattern of gender-based violence, Council members in resolution 1325 agreed that it was important, in the future, to ensure that women’s needs, and therefore their views, were taken into account in the planning and execution of all aspects of conflict prevention, peace processes, peacekeeping operations and post-conflict recovery on the assumption that women had a critically important contribution to make regarding how peace could be achieved and maintained. Put simply, by involving and taking into account the views of half of society a negotiated peace was more likely to be able to be implemented by that society.

Resolution 1325 laid out a normative framework. Furthermore, it asked the Secretary-General to carry out a study on the impact of armed conflict on women and girls, the role of women in peacebuilding and the gender dimensions of peace processes and conflict resolution and to report to the Council.

Resolution 1325 also recognised that women were combatants in many conflicts, and were also a significant part of the support systems to armed groups, and must be paid special attention in demobilisation and reintegration programs. It also highlighted the obligations under international law of parties to conflict to protect women in armed conflict. This aspect was considerably strengthened by subsequent resolution 1820 (2008), in which the Council recognised that systematic sexual violence can significantly exacerbate situations of armed conflict and may impede the restoration of international peace and security. Resolution 1888 (2009) followed up this conclusion and requested the Secretary-General to appoint a Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Conflict. Margot Wallström of Sweden was appointed to this position on 2 February 2010.

Resolution 1325 made some very practical recommendations to the Secretariat and member states:

-

to increase the number of female peacekeepers; and

-

to increase the number of women leaders dealing with issues of peace and security both in national governments and the UN system.

The Council made these recommendations believing that increasing the numbers of women in these functions would improve prospects for peace by: empowering women in conflict through positive female role models; changing the relationship between traumatised civilians and security services by putting a female face on authority; and by offering an alternative perspective in providing solutions to conflict situations.

The normative framework created by resolution 1325 has guided work on gender ‘mainstreaming’ policies (in practical terms taking into account women’s needs and views across a broad spectrum of functions and projects in which the UN is engaged) across the UN system and has thrown a spotlight on issues preventing gender equality within UN agencies.

It also called attention to the Secretary-General’s action plan to have gender equality in the Secretariat by 2000.

The framework also prompted the Council to continue taking up the thematic issue of women, peace and security in the ten years since. In the last three years it adopted three further resolutions on this subject (resolutions 1820, 1888 as well as 1889 which focused on the importance of women’s involvement in post-conflict recovery). In 2010 alone, the Council was expecting five different reports from the Secretary-General stemming from resolutions 1888 and 1889.

Finally, the tenth anniversary of 1325 will be recognised by a ministerial-level open debate of the Security Council in October.

This report demonstrates that during the past decade, the Security Council has attempted to address in a cross-cutting way the issues facing women in conflict (as laid out in resolution 1325) in its consideration of country-specific situations. It has managed to succeed in achieving this in many country situations. But its approach has not been fully systematic. The Council appears to have been considerably more successful in addressing the protection rather than the participation aspects of resolution 1325.

It appears that addressing the impact of conflict on women in specific mandates relies largely on the efforts of a few Council members or individuals within the Secretariat.

Over the years, the Council has lacked consistent, high-level leadership on this issue. Responsibility to mainstream the issue across the broader Council agenda often falls upon junior officers who cover gender issues in their portfolio in the General Assembly. Many come into the Council delegation just to discuss this issue and therefore have little experience in negotiation in the Council context or the country-specific situations. Accordingly, a mainstreaming or cross-cutting methodology is often absent from the delegations.

The changing composition of the Council has also significantly affected the Council’s approach to this issue. Elected members have tended to have a strong influence on Council dynamics.

At press time, negotiations were underway in the Council, ahead of the open debate in October, on an outcome for October. These are focused on the role of the Council in the implementation of resolution 1325 and ways to improve Council working methods in its consideration of women and peace and security across the Council agenda.

top

2000: Resolution 1325 • 2001 – 2007 • 2008: Resolution 1820 on Sexual Violence in Conflict • 2009: Resolutions 1888 and 1889

2000: Resolution 1325

Given that ten years have passed since its negotiation and adoption it is worthwhile to recall how and why the Council came to adopt resolution 1325 in the first place.

An important predecessor was the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995, which adopted a Platform for Action which identified the importance of increased participation of women in conflict resolution. This was reiterated in the 23rd Special Session of the UN General Assembly: ‘Women 2000: Gender Equality, development and peace’, in June 2000, when the results of the review process of the Platform for Action (Beijing+5) were deliberated. While particular attention was paid to women as victims of armed conflict, mention was also made of the under representation of women in decision making positions related to peacekeeping, peacebuilding and post-conflict reconciliation, as well as lack of gender awareness in these areas.

Resolution 1325 came forward in this wider context. It was landmark because for the first time the UN organ with primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security—the Security Council—was considering the importance of women’s role in peace and security.

At the time, there was doubt by some members of the Council about embracing these issues. The eventual adoption of resolution 1325 can be attributed to several factors. In particular the efforts, determination and personal conviction of several individuals serving on the Council at the time: the permanent representatives of Bangladesh, Namibia, Canada, Jamaica and Mali; as well as the influence of women’s NGOs carrying forward the Beijing Platform for Action; all working within an environment of assessment of the UN’s overall approach to peace operations.

Bangladesh came onto the Security Council in January 2000 and was due to hold its presidency in March 2000. Its Ambassador Anwarul Chowdhury was convinced that gender equality was an important key to peace and proposed that the Council should adopt a resolution on the issue whilst Bangladesh had the presidency. He started negotiations within the Council in January but encountered resistance from some Council members, particularly from the P5, at introducing what was considered a ‘soft’ topic onto the agenda of the Council. This came at a time when the Council was hesitantly beginning to develop a number of thematic agenda items. The first related to Protection of Civilians (resolutions 1265 and 1296) and secondly Children and Armed Conflict (resolutions 1261 and 1314).

Bangladesh was unable to get Council support for a resolution or a presidential statement in March, but succeeded in getting members of the Council to agree to a press statement to be issued on the occasion of International Women’s Day, 8 March 2000. The draft press statement, despite its less formal status, was carefully negotiated by the Council. Some members continued to have strong reservations.

The eventual press statement (SC/6816) highlighted the importance of women’s full participation in power structures and the role of women in preserving social order and as peace educators and touches upon several of the elements that would eventually form resolution 1325: full participation of women in all efforts for the prevention and resolution of conflicts, the particular effect of armed conflict on women and girls, awareness of gender-specific human rights abuses, protection for refugee and displaced women, and the importance of a visible policy of mainstreaming a gender perspective in policies and programmes while addressing armed or other conflicts.

Chowdhury subsequently briefed the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) which was in session at the time. While the response was largely positive, some delegates criticised the Council for encroaching on the mandate of the General Assembly, in particular the CSW.

In March 2000 the Council also began to incorporate elements relating to women, peace and security in its wider thematic work and in particular in two presidential statements adopted during the Bangladeshi March 2000 presidency. The first on ‘Maintaining peace and security: Humanitarian aspects of issues before the Security Council’ (S/PRST/2000/7) ‘notes the importance of adequate training for peacekeeping personnel in international humanitarian law and human rights and with regard to the special situations of women and children as well as vulnerable population groups’. The second on ‘Maintenance of peace and security and post-conflict peace-building’ (S/PRST/2000/10) ‘stresses the importance of addressing, in particular, the needs of women ex-combatants, notes the role of women in conflict resolution and peace-building and requests the Secretary-General to take that into account’.

These were the first instances when language of this nature appeared in Security Council decisions and were promoted by Bangladesh with support from other elected members, in particular Canada, Mali, Jamaica and Namibia.

Canada gave prominence to the issue during its presidency in April 2000. Angela King, the Assistant Secretary-General and Special Adviser on Gender Issues and the Advancement of Women, was invited to address the Council during its debate on Afghanistan to discuss and answer questions about the situation facing Afghan women and children under the Taliban. (King was one of the first women ever appointed as a Special Representative and led the UN’s monitoring mission in South Africa, UNOMSA in 1992-94; she had also led the Inter-Agency Gender Mission to Afghanistan in November 1997, the first of its kind to assess the impact of conflict on women in a particular country situation.)

Jamaica during its presidency in July, proposed that the draft resolution on Children and Armed Conflict should include language on the special needs and particular vulnerabilities of girls affected by armed conflict. (It was introduced on the last day of Jamaica’s presidency and adopted on 11 August 2000 as resolution 1314). Jamaica also convened an open debate on the role of the Council in the prevention of armed conflict, chaired by the country’s foreign minister and the outcome document, a presidential statement (S/PRST/2000/25), recognised ‘the important role of women in the prevention and resolution of conflicts and in peace-building’. It also stressed ‘the importance of their increased participation in all aspects of the conflict prevention and resolution process’.

Namibia also gave prominence to the issue in 2000, taking the lead in cooperating with the Lessons Learned Unit of the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) and helping develop the Secretariat’s report Mainstreaming a Gender Perspective in Multidimensional Peace Operations. Namibia co-hosted with the UN a seminar in May that led to the Windhoek Declaration and the Namibia Plan of Action on ‘Mainstreaming a Gender Perspective in Multidimensional Peace Support Operations’ (S/2000/693). Namibia also chaired the 23rd Special Session (Beijing+5) of the General Assembly in June 2000 and was well-versed in the issues. In October, Namibia held the presidency of the Council and led negotiations on a draft resolution. It hosted an Arria-formula meeting on 23 October for members of the Council to meet relevant NGOs. An open S/PV.4208 followed in the Council on 24-25 October. Twenty-three non-Council members participated in this debate. The sustained attention given to the issue by Bangladesh and Namibia along with Canada and Jamaica built momentum throughout 2000 that led to the unanimous adoption of resolution 1325 on 31 October 2000.

In addition to its permanent members, the Council at that time included Argentina, Bangladesh, Canada, Jamaica, Malaysia, Mali, Namibia, the Netherlands, Tunisia and Ukraine. Only Jamaica had a female permanent representative.

The efforts within the Council came against a backdrop of wider efforts by the UN system to consider the question of how and whether to address the gender dimension in peace operations. DPKO had been considering related issues since late 1998, when its Lessons Learned Unit was tasked to prepare the July 2000 report prepared with Namibia (mentioned above). The increasingly multidimensional nature of peacekeeping operations that had been mandated since the late 1980s, and in particular during the 1990s, had led to reflection on the nature of peacekeeping’s role, and how best to mandate the necessary tasks to avert failures of the kind that had occurred in the 1990s. Peacekeeping missions were no longer traditional operations to monitor ceasefires or the implementation of peace agreements and increasingly had a range of components that included in addition to a military contingent, civilian police, political affairs, rule of law, human rights, humanitarian, reconstruction and public information elements.

In May 2000, an NGO Working Group on Women, Peace and Security was formed (combining 14 separate civil society groups) with the goal of advocating for the Security Council to adopt a resolution on the issue. The NGO Working Group conducted advocacy to inform Council members of the relevance of the issue to the work of the Council, maintain pressure, help willing members build momentum and provide guidance to Council members on the eventual drafting of the resolution.

2001-2007

Starting in 2001, the Council met on each anniversary of the adoption of resolution 1325. This usually resulted in a presidential statement reaffirming the Council’s commitment or highlighting a particular aspect of gender considerations in peace operations. Each of these statements slightly refined the emerging normative framework on women, peace and security.

Attention by the Council outside of the ‘anniversary’ debates was rare and usually the result of particular Council members seeking to draw attention to the issue. For example, on 25 July 2002 the UK presidency held a debate where Council members interacted with other UN member states and a Secretariat panel (comprised of Angela King and the heads of the UN Development Fund for Women, or UNIFEM, and DPKO) on the topic of conflict, peacekeeping and gender. During the debate Council members alternated speaking with non-Council members and at any time the Secretariat panel could ask questions of Council or non-Council member states and vice versa. Angela King presented the preliminary results from the Secretary-General’s study on the impact of conflict on women (requested in resolution 1325).

Another innovation was in March 2007 when South Africa also broke out of the ‘anniversary’ pattern proposing a debate on the occasion of International Women’s Day during its presidency. It successfully pushed for the adoption of a presidential statement. This was the first time the Council had spoken on International Women’s Day since 2000.

2008: Resolution 1820 on Sexual Violence in Conflict

In the jurisprudence that came out of the International Criminal Tribunals for the Former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, it emerged that sexual violence had been a specific tactic of war and had been recognised as a constituent act of genocide. It was recognised that even if women survived the level of sexual violence inflicted upon them, and assuming they were able to reproduce after the attack (or repeated attacks) and assuming they were not pregnant with the perpetrator’s baby, the psychological damage to the individual can be irreparable and the social stigma within families and communities insurmountable. In short, combatants had recognised that systematic sexual violence was an effective tool to destroy a community—either of a rival ethnic group or in retaliation for cooperating with their foe. In 2008 the Council, responding to the jurisprudence, also formally recognised the dangers this development presented to international peace and security.

This was preceded in the General Assembly in 2007 when the US led negotiations on ‘Eliminating rape and other forms of sexual violence in all their manifestations, including in conflict and related situations’. The resolution was adopted by consensus (A/RES/62/134), but did not include the stronger language on the use rape in armed conflict that many of its sponsors had hoped.

In the spring of 2008 advocates persuaded key ambassadors to view a documentary film called The Greatest Silence—Rape in the Congo. The film followed a victim of gang rape as she spoke to victims of sexual violence at the hands of foreign militias and the Congolese army in eastern Congo.

The US proposed during its presidency of the Council in June 2008 to take the key elements related to rape and sexual violence in conflict situations in the General Assembly resolution into a new Council resolution on women, peace and security focused on the use of sexual violence in armed conflict as a weapon or tactic of warfare.

There was initially resistance in the Council to a new resolution on women, peace and security, including from key advocates of resolution 1325. Some considered that a new resolution that just focused on sexual violence would dilute the wider focus of the landmark 1325, which had not ignored this issue (it was mentioned in operative paragraphs 10 and 11). There was particular concern the draft would weaken support for women’s increased participation in leadership positions in resolution 1325, as it highlighted women’s vulnerability (or weakness). Others in the Council assessed that singling out sexual violence in conflict was unhelpful, given the range of other forms of violence specifically perpetrated against women during periods of conflict—such as murder and maiming.

However events on the ground in the DRC played an important role in shifting Council dynamics on this issue. Evidence of widespread, systematic, brutal and highly publicised sexual violence perpetrated against the women of the eastern DRC increased support in the Council for the US initiative.

On 19 June 2008 US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, chaired an open debate of the Security Council, after which the Council unanimously adopted resolution 1820. For the first time the Security Council identified sexual violence when used or commissioned as a tactic of war in order to deliberately target civilian populations or as part of a widespread or systematic attack against civilian populations as an impediment to international peace and security.

The elected members of the Council at the time were: Belgium, Burkina Faso, Costa Rica, Croatia, Indonesia, Italy, Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, Panama, South Africa and Viet Nam. No Council member had a female permanent representative.

2009: Resolutions 1888 and 1889

On 30 September 2009 US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton chaired a meeting on sexual violence in armed conflict, as a follow up to resolution 1820. The meeting was public, but only Council members could speak. At this meeting the Council adopted resolution 1888, which recommended the Secretary-General appoint a special representative to implement resolution 1820.

One week later the Council took up the wider resolution 1325 agenda on 5 October 2009. Viet Nam’s Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs Pham Gia Khiem presided over an open debate on women, peace and security. The Council adopted resolution 1889 which called upon the Secretary-General to submit to the Security Council a set of indicators for use at the global level to track implementation of resolution 1325. The Secretary-General submitted a preliminary set in April 2010, with a revised set expected in September 2010. (The Council is expected to take action on the indicators in October 2010.)

Resolution 1889 had a slightly complicated origin. Viet Nam had signalled early on its intentions to propose a resolution on women, peace and security during its presidency in October 2009, on the importance of women’s involvement in post-conflict recovery. Viet Nam wanted to draw upon the lessons it had learned emerging from conflict and highlight the importance of women’s education and other development issues. There was some resistance to such direct references to economic and social dimensions. There was also procedural resistance to adopting a second resolution so soon after resolution 1888. Some thought a presidential statement highlighting the importance of the upcoming tenth anniversary of resolution 1325 would be sufficient. Viet Nam was firm about a resolution. After detailed negotiations a draft resolution was agreed highlighting women’s role in post-conflict peacebuilding efforts and the impediments to women’s involvement and seeking, in addition to the indicators, a report from the Secretary-General on women in peacebuilding, to be drafted in coordination with the Peacebuilding Support Office (PBSO).

top

3. Women, Peace and Security: the Normative Framework

During the last decade the Council has established a wide normative framework under the theme of women, peace and security through its four resolutions and nine presidential statements. This framework now forms the mandate that directs Secretariat action on this issue, guides the Security Council approach, provides guidance and precedent for broader UN member state action on and consideration of the issue and establishes a set of generally accepted principles for handling the matter.

It is worthwhile to analyse this normative framework through a closer look at resolutions 1325, 1820 and the associated resolutions and presidential statements, prior to embarking on an analysis of how effectively the Council has incorporated this issue into its working methods and practice when considering country-specific and other thematic decisions. (See Annex I for a detailed analysis of the text of resolutions 1325 and 1820.)

Resolution 1325

There are essentially six sections in resolution 1325.

The first section (operative paragraphs 1-4) deals with increasing women’s participation in decision-making on the prevention, management and resolution of conflict: in national, regional and international institutions and in the UN system. It also urges an increase in the number of women appointed as special representatives and envoys to pursue good offices functions on behalf of the Secretary-General and in UN field-based operations, especially among military observers, civilian police, human rights and humanitarian personnel.

The second section of resolution 1325 (operative paragraphs 6-7) addresses capacity issues by focusing on developing guidelines and materials to train military, police and civilian personnel deploying with UN peace operations regarding the importance of involving women in all peacekeeping and peacebuilding activities, as well as on the protection, rights and particular needs of women; and increasing financial, technical and logistical support for gender-sensitive training.

The third section (operative paragraph 8) goes into detail on the specific areas where gender should be considered with respect to negotiating and implementing peace agreements: the special needs of women and girls during repatriation and resettlement and for rehabilitation, reintegration and post-conflict reconstruction; measures that support local women’s peace initiatives and indigenous processes for conflict resolution and measures that involve women in all of the implementation mechanisms of the peace agreements; and measures that ensure the protection and respect for human rights of women and girls, particularly as they relate to the constitution, the electoral system, the police and the judiciary.

The fourth section (operative paragraphs 9-11) focuses on the international legal framework relevant to the protection of women and girls as civilians, calling on all parties to armed conflict to: respect fully international law in this regard including their obligations under the Geneva Conventions, the Convention related to the Status of Refugees, Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), Convention on the Rights of the Child and the relevant provisions of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC); take special measures to protect women and girls from gender-based violence, particularly rape and other forms of sexual abuse, and all other forms of violence in situations of armed conflict; and goes on to emphasise the responsibility of all states to put an end to impunity and prosecute those responsible for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes, including those relating to sexual and other violence against women and girls and stresses the need to exclude these crimes, where feasible, from amnesty provisions.

The fifth section (operative paragraphs 12-13) outlines two practical areas for action on gender issues: respecting the humanitarian nature of refugee and internally displaced persons (IDP) camps, taking into account the particular needs of women and girls in camp design; and the different needs of women ex-combatants and the needs of their dependants when planning DDR programmes.

Finally in the sixth section resolution 1325 commits the Council to using guidelines for its approach to gender issues across the broader Council agenda. In particular, the Council expresses its willingness to:

-

incorporate a gender perspective into peacekeeping operations (operative paragraph 5);

-

ensure that Council visiting missions take into account gender considerations and the rights of women, including through consultation with local and international women’s groups (operative paragraph 15); and

-

take into account, whenever sanctions are adopted under article 41 of the Charter, their potential impact on the civilian population, bearing in mind the special needs of women and girls, in order to consider appropriate humanitarian exemptions (operative paragraph 14).

It has become shorthand when referring to the content of resolution 1325 to say that it covers women’s participation and protection in situations of armed conflict. While this is the resolution’s main thrust, its scope is more complex than just participation and protection. Some issues, such as the demobilisation of female combatants or women voluntarily or involuntarily associated with armed groups, can fall into both (or neither) categories depending on the context. Generally, resolution 1325 is balanced between increasing women’s participation in all aspects of action and decision-making relevant to peace and security, and highlighting women’s rights and the importance of protecting women as a vulnerable subset of broader protection of civilian considerations.

Presidential Statements on Women, Peace and Security

Prior to the adoption of resolution 1820 in 2008, the scope of the resolution 1325 framework was supplemented by seven presidential statements. Most language in the presidential statements reiterated aspects of resolution 1325 or acknowledged particular achievements of women’s participation or gender mainstreaming within the UN system. Some elements were procedural requesting new reports from the Secretary-General on the implementation of resolution 1325 (including outlining obstacles to increased participation of women in conflict prevention, conflict resolution and peacebuilding) or on the impact of armed conflict on women. In contrast to earlier years, the latest requests for information on the impact of armed conflict on women were restricted to situations on the agenda of the Security Council (2007 and 2008).

Some presidential statements made small additions to the normative framework, including (in 2002) a condemnation of all violations of the human rights of women and girls in situations of armed conflict, and the use of sexual violence, including as a strategic and tactical weapon of war. This was a significant step further than resolution 1325 and a concept taken up directly by resolution 1820.

Specific additional requests to the Secretary-General included:

-

(in 2002) integrate gender perspectives into all standard operating procedures, manuals and other guidance material for peacekeeping operations; and include gender specialists in the teams of Council visiting missions where relevant;

-

(in 2004) ensure that human rights monitors and members of commissions of inquiry have the necessary expertise and training in gender-based crimes and in the conduct of investigations, including in a culturally sensitive manner favourable to victims; consider appointing a senior gender adviser within the Department of Political Affairs (DPA); ensure all policies and programmes in support of post-conflict constitutional, judicial and legislative reform, including truth and reconciliation and electoral processes, promote the full participation of women, gender equality and women’s human rights;

-

(in 2005) ensure that all peace accords concluded with UN assistance address the specific effects of armed conflict on women and girls, as well as their specific needs and priorities in the post-conflict context, underlining in this context the importance of broad and inclusive consultation with civil society in particular women’s organisations and groups; and

-

(in 2006) collect and compile good practices, lessons learned and identify remaining gaps and challenges in order to further promote the efficient and effective implementation of resolution 1325, in the context of increasing women’s participation in decision-making.

Broader requests by the Council addressed to the international community as a whole included:

-

(in 2002) encouraging relevant actors to include gender perspectives in humanitarian operations, rehabilitation and reconstruction programmes, and also to develop targeted activities, focused on the specific constraints facing women and girls in post-conflict situations, such as their lack of land and property rights and access to and control over economic resources;

-

(in 2004) urging all international and national courts specifically established to prosecute war-related crimes to provide gender expertise, gender training for all staff and gender-sensitive programmes for victims and witness protection;

-

(in 2007) emphasising the importance of strengthening cooperation between member states and between the UN and regional organisations in adopting and promoting regional approaches to implementing 1325.

Resolution 1820

The concepts of resolution 1820 derive from, and significantly elaborate upon, the Council’s previous decisions on protection of civilians, as well as the more limited protection aspects included in resolution 1325.

There were several elements in resolution 1820 that break new ground for a Council resolution. In it, the Security Council:

-

concluded that sexual violence when used or commissioned as a tactic of war in order to deliberately target civilian populations or as part of a widespread or systematic attack against civilian populations may impede the restoration of international peace and security;

-

demanded the cessation by all parties to armed conflict of acts of sexual violence against civilians; and

-

affirmed its intention (which it had already expressed in two specific cases—the DRC and Côte d’Ivoire) when establishing and renewing state-specific sanctions regimes, to consider targeted sanctions and other graduated measures against parties to situations of armed conflict who commit rape and other forms of sexual violence against women and girls in situations of armed conflict.

Resolution 1820 also considerably expanded upon the legal dimensions addressed by resolution 1325 in several ways. It listed the possible measures parties could take to protect women and children from sexual violence; reinforced measures ending impunity. It noted that rape and other forms of sexual violence can constitute a war crime, a crime against humanity or a constitutive act with respect to genocide. It also reinforced the capacity components of resolution 1325, in particular the need to develop and deliver training for peacekeeping and humanitarian personnel deployed by the UN to better prevent, recognise and respond to sexual violence and other forms of violence against civilians.

While resolution 1820 included some mention of women’s involvement in peace processes it was in the context of addressing sexual violence that occurred during the conflict in question. Likewise, women’s involvement in post-conflict peacebuilding efforts was addressed in the context of protection of women in IDP camps, throughout demobilisation and reintegration programmes and in justice and security sector reform and addressing the long-term consequences of sexual violence in rebuilding society.

Resolution 1888

Resolution 1888 builds on resolution 1820. Over half of its operative paragraphs directly reinforce previous language from resolution 1820, some of which was in turn drawn from resolution 1325.

The key new elements of resolution 1888 were a range of measures to develop capacity to staff the implementation of resolution 1820. These included:

-

a request for the Secretary-General to appoint a Special Representative on sexual violence in conflict;

-

a request to deploy rapidly a team of experts to situations of particular concern with respect to sexual violence in armed conflict;

-

a decision to include specific provisions in peacekeeping mandates, as appropriate, for the protection of women and children from rape and other sexual violence, including the identification of women’s protection advisers among the gender adviser and human rights protection units in peacekeeping missions.

Resolution 1888 also stated that the Council would review the mandates of the Special Representative and the team of experts within two years, taking into account the establishment of the new UN gender entity (UN Women) in 2011.

Other new elements included: urging states to undertake comprehensive legal and judicial reforms with a view to bringing perpetrators of sexual violence in conflict to justice and ensuring appropriate treatment of survivors of sexual violence; urging parties to a conflict to ensure that all reports of sexual violence committed by civilians or by military personnel are thoroughly investigated and civilian superiors and military commanders use their authority and power to prevent sexual violence; encouraging states to increase access to the necessary support services for victims of sexual violence; encouraging local and national leaders, including traditional and religious leaders, to play a more active role in sensitising communities on sexual violence to avoid marginalisation and stigmatisation of victims; urging Special Representatives and the Emergency Relief Coordinator of the Secretary-General to work with member states to develop joint government-UN comprehensive strategies to combat sexual violence; and encouraging increased briefings and documentation on sexual violence in armed conflict to the Council.

Resolution 1888 also requested the Secretary-General to devise urgently and preferably within three months, specific proposals on ways to ensure monitoring and reporting in a more effective and efficient way within the existing UN system on the protection of women and children from rape and other sexual violence in armed conflict and post-conflict situations. (At press time it was unclear what formal action the Secretary-General had taken on this request, beyond the appointment of Special Representative for Sexual Violence in Conflict, Margot Wallström, on 2 February 2010.)

Further to the above request, the Council also requested a report from the Secretary-General on implementation of resolutions 1820 and 1888 by September 2010. The Secretary-General sought an extension of the deadline for the submission of this report, and it is now due to the Council in December 2010.

Resolution 1889

Resolution 1889 focused on the question of how to implement a key feature of resolution 1325, i.e. the increased participation of women in negotiating and implementing peace processes and in other aspects of post-conflict peacebuilding, by identifying obstacles to their full participation and seeking to address those obstacles. Resolution 1889 also looked toward the tenth anniversary of 1325 in 2010 as an opportunity to renew commitments to its implementation.

The bulk of resolution 1889 reinforced key elements and language of resolution 1325.

In resolution 1889 for the first time the Council urged Member States, UN bodies, donors and civil society:

-

to ensure women’s empowerment is taken into account during post-conflict needs assessments and planning, and factored into subsequent funding disbursements and programme activities;

-

to take all feasible measures to ensure women and girls’ equal access to education, given the vital role of education in the promotion of women’s participation in post-conflict decision making; and

-

requested the Secretary-General to ensure full cooperation and coordination between the Special Representative for Children and Armed Conflict and the Special Representative for Sexual Violence in Conflict.

Resolution 1889 also requested three separate reports from the Secretary-General. The first request was for a set of indicators for use at the global level to track implementation of resolution 1325, which could serve as a common basis for reporting by relevant UN entities, other international and regional organisations and member states. (A preliminary set of 26 indicators was submitted to the Council in April 2010. The Council decided in a presidential statement that same month that these indicators needed increased technical and conceptual development and requested the Secretary-General to continue to work with the Security Council on them and to consult with the broader UN membership with a view to submitting a revised set in September 2010. The Council expressed its intention to take action on the indicators in October 2010.)

The second request in resolution 1889 was for the Secretary-General’s report on the implementation of the 2008-2009 UN System-Wide Action Plan on the implementation of resolution 1325 (requested by the Council in 2007, due in September 2010) to include an assessment of the processes by which the Security Council receives, analyses and takes action on information pertinent to resolution 1325, recommendations on further measures to improve coordination across the UN system, and with member states and civil society to deliver implementation, and data on women’s participation in UN missions. (It is expected that this report will also include the revised indicators referred to above and come out in September 2010.)

The third request in resolution 1889 was for the Secretary-General to submit a report to the Security Council by October 2010 on addressing women’s participation and inclusion in peacebuilding and planning in the aftermath of conflict, taking into account the views of the Peacebuilding Commission (PBC). The Secretariat undertook wide consultations on this report throughout 2010. The report is expected to be submitted to the Council in October. It is expected this report will be considered by the Council at the same time as the indicators.

In conclusion, therefore, it seems reasonable given the wide scope of this normative framework to expect to see references to the issues of women, peace and security in all Security Council peace operation mandates. In particular, based upon the normative framework, one would expect to see references specifically to women when the Council considers peace mediation, peace negotiations, implementing peace agreements, the design and execution of disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR) programmes and DDR and repatriation (DDRR) programmes, mine action, security sector and justice reform, monitoring human rights situations, monitoring the situation of refugees and internally displaced persons and electoral planning to increase women’s participation (both as candidates and voters). It is reasonable to expect the Council to reinforce the importance of increasing the number of women in UN entities responsible for implementing the above mandates, especially in military and police components and in mission leadership positions.

One might also reasonably expect to see the framework reflected in other Council action on country-specific issues at different stages of the conflict cycle, including conflict prevention, preventive diplomacy, conflict resolution or peacebuilding.

top

Brief Outline of UN System Responses to Implement Resolution 1325

4. Cross-Cutting Analysis: Resolutions

Research Methodology

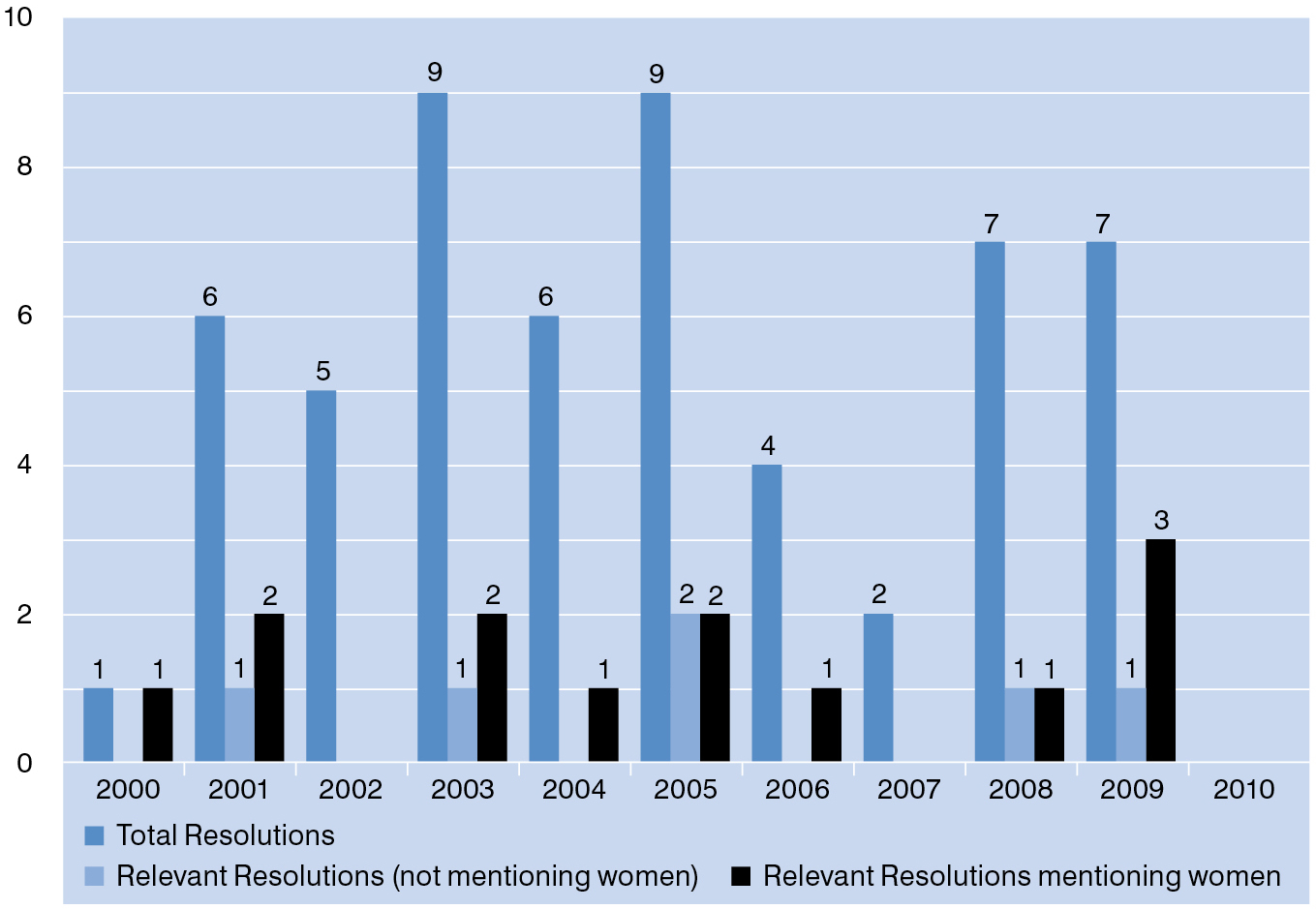

In collating the following data in order to test whether cross-cutting expectations have been met, we analysed Council resolutions from the period from November 2000 to August 2010. We separated the resolutions into the categories of: total number of resolutions; resolutions where one might reasonably expect to find a reference to the topics covered in resolution 1325 (or after their adoption to resolutions 1820, 1888 or 1889); and resolutions where indeed a reference to the topics covered in resolution 1325 (and associated resolutions) was found.

Given the breadth of relevant issues covered by resolution 1325, references to at least some of these might be expected in all country-specific resolutions. In particular references in resolutions that established or altered the mandate of peacekeeping operations seemed reasonable, given that in resolution 1325 the Council expressed ‘its willingness to incorporate a gender perspective into peacekeeping operations, and urged the Secretary-General to ensure that, where appropriate, field operations included a gender component’. (See Annex II for specific references to women, peace and security elements in peace operation mandates and resolutions renewing mandates from 2000 to 2010.)

A resolution containing only a reference to, say, ensuring HIV awareness amongst peacekeepers or to the Secretary-General’s zero tolerance approach to sexual abuse and exploitation by peacekeepers was not considered as meeting the test. While both are important issues for the Council to address and reinforce, we considered each to be tangential to the scope and intent of resolution 1325.

In our analysis we categorised the following as thematic issues: UN peace operations (including the relationship between the Security Council and troop contributing countries), conflict prevention/mediation/peacebuilding (including the role of the PBC), the Security Council’s relationship with regional organisations (such as the African Union), protection of civilians, counter-terrorism, small arms and light weapons, children and armed conflict and non-proliferation.

Country Situations

The analysis shows that there has been a gradual increase in the number and quality of references to women, peace and security in Council resolutions on country situations. The period 2001 to 2006 saw a gradual increase from 22 percent to a steady plateau of around 30 percent (with a spike to 40 percent in 2003).

There was a significant change from the start of 2007. The Council moved from including a reference to women in 11 out of 38 relevant resolutions in 2006, to including such a reference in 20 of the 34 relevant resolutions in 2007. In other words, the number of references jumped from 30 to 60 percent in one year.

References increased further in 2008 (67 percent) and 2009 (73 percent). In January-August 2010, 13 of the 16 (or 81 percent) resolutions adopted by the Council on country-specific situations have included a reference to women, peace and security.

Composition of References in Resolutions

The detail of specific references to women, peace and security has varied widely over the decade. For example, some resolutions have only included a specific preambular reference to resolution 1325, with no further reference to women in the operative section of the resolution.

Early on, there appeared to have been a tendency for women’s participation to be encouraged in the preambular sections, where the Council usually would highlight a particular achievement of a women’s group described in the related Secretary-General’s report, for example the consistent references to the Mano River Women’s Peace Network in resolutions on Liberia and Sierra Leone from 2001-2003 or the efforts of Somali women in 2006. The references to women in the operative sections almost always focused on protection, as most often these references were expanding or reinforcing an existing mandate.

Since 2007, references to women became more consistent across country situations on the Council’s agenda. Since 2007 women, peace and security issues have been reflected consistently in all the resolutions on the situations in: Côte d’Ivoire, Nepal, Haiti, Timor-Leste, Afghanistan, Liberia, Sudan (both Darfur, and north/south issues), Chad/Central African Republic, Burundi, Sierra Leone and Guinea-Bissau. References to women, peace and security had been included in almost all resolutions on the DRC (nine out of 11) and Somalia (seven out of eight).

This compares to the period of 2000-2006 where there were no country situations that consistently contained a reference to women, peace and security. In most country situations, half or less than half, of the resolutions issued contained a reference. For example: Côte d’Ivoire (five out of 11); Haiti (three out of six); Timor-Leste (two out of seven); Liberia (three out of eight); Burundi (three out of eight) and Sierra Leone (seven out of 14). Notably, over this period for resolutions on the DRC, only eight out of 21 contained a reference to women.

The Council has never included a mention of women, peace and security in its resolutions on the situations in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Georgia, Kosovo, Croatia, Western Sahara, Cyprus or Ethiopia/Eritrea. There has not been a reference in the resolutions on the situation in Lebanon since expanding the mandate of the UN Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) in 2006.

Beyond these overall trends, several noteworthy patterns emerge:

-

the Council first expressed its concern over the level of sexual violence against women in its resolution 1370 (2001) on the situation in Sierra Leone;

-

resolution 1410 (2002) that established the UN Mission of Support in East Timor (UNMISET) was the first resolution to recognise ‘the importance of a gender perspective in peacekeeping operations and mandated a focal point for gender to be included within its civilian component;

-

the first resolution to mention resolution 1325 following its adoption was resolution 1445 (2002) renewing the UN Organization Mission in the DRC (MONUC) mandate;

-

resolution 1445 on the DRC also saw the start of a trend to include vague language on including gender ‘perspectives’ or the importance of ‘gender mainstreaming’ in Council resolutions, without identifying elsewhere in the mandate the specific areas where gender was relevant or the action required;

-

the Council has only once encouraged a specific mission to increase the number of female peacekeepers. This came in 2003 in resolution 1493 regarding MONUC, when the Council called upon MONUC to increase the deployment of women as military observers as one response to address the use of violence against women and girls as a tool of warfare;

-

a preambular reference to resolution 1325 (without its title ‘women, peace and security’) appeared in UNIFIL resolutions in 2003; it continued to stay in the mandate extensions until 2006; starting with resolution 1701, there have been no mentions at all of resolution 1325 or women;

-

UNMIS is the only situation that has consistent references to women’s participation without also referring to protection, in the context of the importance of women’s involvement in implementing the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA);

-

the Council has only once called upon an operation to develop a gender equality strategy in cooperation with national authorities: in the mandate of UN Integrated Mission in Timor-Leste (UNMIT) established in 2006 through resolution 1704;

-

the Council has mandated the head of a peacekeeping operation to identify women’s protection advisers in the case of one peace operation, MONUC in 2009 (also included in the mandate of its successor mission, MONUSCO).

Thematic Resolutions

The Council has adopted 19 relevant thematic resolutions since the adoption of resolution 1325. Of these, 13 contained a reference to women, peace and security issues. Three of these were specifically on women, peace and security (resolutions 1820, 1888 and 1889). The remaining ten were on the topics of protection of civilians (three), children and armed conflict (three), conflict prevention (two), peacebuilding (one) and peace operations (one).

While the Council has consistently considered this issue over the period from 2000 to 2010, it has not always reflected it in relevant thematic resolutions. The Council has never mentioned women, peace and security elements in its resolutions on small arms and light weapons, nor on cooperation between the UN and regional organisations, particularly in the context of joint peacekeeping operations (see resolutions 1631 of 2005 and 1809 of 2008), nor in its 2001 resolution on the relationship between the Council and troop contributing countries (resolution 1353).

It is perhaps surprising that the Council has omitted women, peace and security issues from its consideration of cooperation between the UN and regional organisations, given the emphasis of these resolutions on the role of regional organisations, in particular the African Union (AU) in mediation, peace negotiations, peacekeeping operations and post-conflict recovery¾all prominent areas of resolution 1325. For example resolution 1809 (2008) considered, amongst a range of issues, the importance of the AU’s role in conflict mediation without mentioning resolution 1325. Also many AU peacekeeping missions have evolved into UN peacekeeping missions, often with the same troop contributors.

There is a strong overlap between the issues of resolution 1325 and children and armed conflict, in particular the effect of conflict on girls. Despite that overlap the Council has not drawn a link to resolution 1325 in its last two resolutions on children and armed conflict, including in the key resolution on this agenda item, resolution 1612 of 2005, which established a Council working group on this issue.

top

5. Cross-Cutting Analysis: Presidential Statements

Research Methodology

The analysis also covers presidential statements. Presidential statements, while often brief, are as carefully negotiated as resolutions. They are usually adopted when there are significant developments on the ground in country situations on the Council’s agenda, or to reinforce important points following open debates or the release of key documents by the Secretariat. The language in presidential statements is useful to analyse, as it is often less formulaic than resolutions and as such can reflect the mood of the Council on a given issue.

Since many presidential statements are issued in response to a particular event, we have considered carefully which statements should reasonably include a reference to women, peace and security. We have considered relevant those that discuss a country situation where the issues of resolution 1325 are part of the mandate of the peace operation or could be a prominent aspect of the development on the ground. We have also considered relevant those presidential statements that take the opportunity to reinforce key general points, where one might reasonably expect to see the issues of resolution 1325 reinforced or reiterated.

To remain consistent in our analysis between resolutions and presidential statements we have categorised the statements issued to condemn particular terrorist incidents as thematic, despite their often country-specific nature.

Country Situations

The analysis concludes that a relatively low number of relevant presidential statements contain references to women, peace and security. The lowest point was 2003 when there were no references. The highest point was 2009 when close to 30 percent contained a reference. So far in 2010 one (out of two) relevant country-situation presidential statements (issued in February on Guinea) contained a reference to resolution 1888, reiterating ‘the call it made in its resolution 1888 (2009) to increase the representation of women in mediation processes and decision-making processes with regard to conflict resolution and peacebuilding’.

Analysis

The years with the highest number of resolutions mentioning women, peace and security issues, such as 2003 and 2007, correspond to the years with the lowest number of presidential statements, suggesting that the Council was reinforcing its key points in resolutions rather than presidential statements in those years.

The references to the women, peace and security vary significantly in quality between different statements. Some, such as that quoted above on Guinea, are specific to issues raised in 1325 or a related resolution, whereas others may simply call upon the women in a given country to vote in an upcoming election.

Over the past ten years the Council has included a reference to women, peace and security in the presidential statements it has issued on Liberia, Kenya and Zimbabwe (one statement has been issued for each in the last ten years). References to women were sporadic in statements issued on other country situations: Great Lakes/Uganda (three out of four); DRC (five out of thirty); Kosovo (two out of 11); Somalia (four out of 22); Sudan (one out of nine); Afghanistan (three out of eight); Haiti (one out of nine); Sierra Leone (one out of three); Burundi (one out of 15); and Chad/CAR (one out of 13). Not one of the 19 presidential statements issued on Côte d’Ivoire mentioned women, peace and security issues.

Thematic Presidential Statements

A significant proportion of thematic presidential statements include a reference to issues relevant to women, peace and security. For example in 2002 six out of seven relevant thematic statements included a reference, in 2005 it was six out of nine. In the first eight months of 2010, six out of eight relevant presidential statements included a reference to the issues covered by 1325 or its related resolutions.

Analysis

The thematic topics covered by presidential statements are wide. Those that have included references to the issues of 1325 include post-conflict peacebuilding, small arms and light weapons, protection of civilians, children and armed conflict, peacekeeping policy, justice and the rule of law, security sector reform, mediation, and preventive diplomacy. Those where one might have expected to see reinforcement of the issues of resolution 1325, but where there was no mention, include the UN’s relationship with regional organisations, the role of civil society in the prevention and pacific settlement of disputes and some key statements on small arms, peacebuilding (including S/PRST/2005/30 that fed into the eventual mandate of the PBC) and peacekeeping policy, such as the most recent presidential statement on the importance of developing transition and exit strategies (S/PRST/2010/2).

top

6. Cross-Cutting Analysis: Mission Mandates

This section analyses whether the Council has incorporated gender issues in its mandated field missions. Council-mandated missions can include peacekeeping operations, special political missions and peacebuilding support missions. DPKO administers and directs peacekeeping operations. DPA administers and directs special political missions and peacebuilding support missions. The only current exception is the UN Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA), which is a political mission directed by DPKO.

With two exceptions, all new mission mandates established by the Council since the adoption of 1325 have included a reference to women, peace and security issues. The peacebuilding operation, BINUCA, established in the Central African Republic in 2009 (via a presidential statement rather than a resolution) has a mandate focused on implementation of the peace process, political dialogue and DDR, however does not mention women. The other exception was UNAMA’s first mandate established in 2002 through resolution 1401 which included no reference at all to resolution 1325 or women. This was a striking omission, as all previous resolutions on Afghanistan had included at least a reference to the human rights situation facing women under the Taliban. This omission was subsequently rectified by the Council and the most recent renewal of UNAMA’s mandate includes monitoring the human rights situation facing women, as well as numerous references to women’s involvement in political and government institutions and protection and human rights issues relevant to women and girls.

A significant proportion of resolutions establishing and renewing Council-mandated missions contain a reference to women, peace and security issues (see the table below). However, there are several missions where this is consistently not the case. For example the mandates and renewals of the UN Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP), the UN Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO) and UNIFIL do not mention women, peace and security, despite the mandates of these missions including issues covered by resolution 1325, such as peace negotiations, implementation of peace agreements and post-conflict community reconciliation (UNFICYP, MINURSO) or are significant peacekeeping operations where the mission should reasonably consider a gender perspective in fulfilling its mandate, such as UNIFIL (which is also mandated to undertake mine action). The UN Mission in Nepal (UNMIN) has a narrow mandate regarding the implementation of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) and arms monitoring. Yet the Council at least included in UNMIN’s mandate a preambular reference to recognising the need to pay special attention to the needs and the role of women in the peace process, as mentioned in Nepal’s CPA and resolution 1325.

See Annex II for a breakdown of the mandates of current missions established or renewed since the adoption of resolution 1325.

Summary of Council Mandated Missions

The increase in references to women, peace and security in Council mandates seems to reflect the increase in the number of missions with integrated mandates, (i.e. where all UN entities also come under the authority of the Special Representative heading the mission) and also the increasingly wide range of tasks missions have been mandated to undertake. Missions can be mandated to work with host authorities on a wide range of capacity building programmes, including to improve rule of law through security sector reform and justice reform and assist local authorities with human rights monitoring, IDP and refugee resettlement and mine action, as well as more traditional functions such as monitoring and assisting the implementation of peace agreements.

There have also been several missions where the UN is authorised under Chapter VII to undertake particular functions on behalf of the government in question or, in Kosovo and Timor-Leste (prior to 2002), to act as the government. When the UN is undertaking executive functions it is an opportunity for the Council to mandate the UN to implement directly aspects of resolution 1325 related to gender equality.

top

7. Timor-Leste Case Study: Successful Gender Mainstreaming and Steps Toward Equality

Since 1999 the UN has had a significant role in Timor-Leste. The UN’s role has involved preparations for the referendum in August 1999 and responding to the post-referendum violence, establishing a major peacekeeping mission and creating innovative new machinery for transitional administration and building the structures for an emergent state from 1999 to 2002. The UN has been working with and supporting an independent Timor-Leste since 2002. Since 1999 the UN has had five consecutive peacekeeping or political missions in the country. The current integrated mission in Timor-Leste (UNMIT) established in August 2006 was the first globally, and to date only, UN peacekeeping operation with a specific mandate to work together with United Nations agencies, funds and programmes, to support the development of a national strategy to promote gender equality and empowerment of women.

UNMIT’s mandate also includes enhancing democratic governance and political dialogue, supporting electoral processes (including parliamentary, presidential and local elections), providing support and training to the national police (effectively rebuilding the leadership that collapsed in 2006), enhancing the effectiveness of the justice system and security sector, assisting national capacity for the monitoring, promotion and protection of human rights and cooperation and coordination with UN agencies, funds and programmes to maximise assistance in post-conflict peacebuilding and capacity building.

There are many challenges to gender equality and the protection of women in Timor-Leste, in particular persistently high levels of domestic violence. The post-referendum violence in 1999 was marked in particular by attacks against women by pro-integration militia, including documented murders of nuns and other civilian women. There had been a history of women’s involvement in the insurgent army, Falintil, and its support networks during Indonesian occupation. Women were known as effective runners, bringing food and information to fighters in hiding. As a result there were many women, as combatants and in support roles, in the Falintil cantonment sites created by the first international stabilisation forces to arrive in 1999. However, very few women were integrated when Falintil fighters were integrated into the national army established upon independence.

The violence in and around Dili of 2006 led to significant internal displacement, which at its peak saw close to 100,000 people living in IDP camps. Further unrest in other population centres in both the west and east in 2006 and 2007 saw further displacement. Increased incidents of violence against women occurred in the IDP camps as well as in communities when the displaced returned home. The IDP camps were gradually all closed. However it is estimated by UNMIT that currently domestic violence cases comprise over one-third of all cases pending before national courts.

The leadership of UNMIT has consistently sought to achieve gender mainstreaming throughout the implementation of its mandate. This has been supported by an active gender adviser role in the mission and by DPKO at UN headquarters. The UNMIT public information unit has also been an important tool. The DPKO desk officer responsible for Timor-Leste during the establishment of UNMIT had previously worked for UNIFEM, and helped to ensure that parties implementing the mandate were aware of the importance of taking gender into account. It seems that UNMIT has been very effective with UN funds and programmes in Dili, especially UNIFEM and UNDP on a range of gender specific programmes and projects.

Rule of Law: Justice System and Police

UNDP has a long-term programme in Timor-Leste to support capacity-building in the justice sector. UNDP supports a Legal Training Centre which by the end of 2009 had trained 13 national judges (four women), 13 prosecutors (six women) and 11 public defenders (three women).

UNMIT has supported active recruitment of women to the National Police of Timor-Leste (Policia Nacional de Timor-Leste, or PNTL). Women currently comprise 20 percent of the police force. The country’s first female district commander (in the district of Liquica) was appointed on 7 September 2010. In order to specifically deal with the problem of violence against women, UNMIT facilitated the establishment of a Vulnerable Persons Unit to deal primarily with gender-based crime, made up principally of women PNTL officers. With the support of the United Nations, child- and victim-friendly interview rooms were established in Vulnerable Persons Units in five districts. UNMIT has also consistently pushed police contributing countries to provide more female police. However, currently only 52 out of 928 community police in UNMIT are female.

The situation is less positive for women in the national military. In early 2009 women constituted 9 percent of the army. A recent recruitment campaign had a goal of attracting 10 percent women as new recruits. Only 7 percent recruited were women (none of whom were selected for the officer programme).

Supporting Women’s Increased Role in Decision Making

Following the 2007 parliamentary elections, women hold 29 percent of seats in Parliament, drawn from the spectrum of political parties. This was due to the requirement that political parties put forward at least one woman candidate out of four on their party lists. The deputy speaker of parliament is a woman.

Women hold three ministerial positions in the current coalition government in the portfolios of finance, justice and social solidarity, as well as the positions of prosecutor-general, vice minister for health and secretary of state for the promotion of equality.

In the village (suco) elections in 2009, 11 women were elected as suco chiefs (442 sucos in the country), and 37 women were elected as hamlet (aldeias) chiefs (2,225 aldeias). The relatively poor result for women at the suco and aldeia level, compared to the national outcome, demonstrated that many cultural and structural barriers remain to women in local politics (including patriarchal traditions at the local level and a lack of childcare).

UNIFEM and the UN Development Programme (UNDP) have a range of projects in Timor-Leste to support women’s active involvement in politics.

UNIFEM’s ‘Integrated Programme for Women in Politics and Decision Making’ aims to promote gender equality by increasing women’s participation in politics and in decision-making at the national, district, suco and aldeia levels. At the national level, the programme involves providing training and support to female parliamentarians, support for the women’s wings of political parties and the resourcing of a Gender Resource Centre at the national parliament (that assists in providing gender-sensitive analysis of national budgets).

UNDP’s closely related project, ‘Strengthening Parliamentary Democracy in Timor-Leste’ provides support to parliamentary standing committees and individual parliamentarians to draft, scrutinise and amend bills as well as analyse and present their policy implications. The project also assists parliament to communicate its work to the public and promote the empowerment of women.

UNDP, UNIFEM, UNMIT and the secretary of state for the promotion of equality supported the parliamentary women’s caucus in the development of a five-year plan (2008-2012) to mainstream gender in the work of the national parliament.The Special Representative has an active programme of meetings with key political actors to support ongoing high-level political dialogue in which the gender element of the Security Council mandate plays an important role. As part of this programme, the Special Representative meets the parliamentary women’s caucus on a regular basis.

Gender in Timorese Policymaking and the Role of the Civil Society

UNMIT and UNIFEM have worked closely on policies to incorporate gender across the activities of the Timorese government, in order to implement UNMIT’s mandate to support the Timorese develop a national strategy to promote gender equality and the empowerment of women. The implementation of this strategy was strengthened by a decision by Timorese authorities in March 2008 to create gender focal points across all Timorese government ministries. These gender focal points have developed sector-wide policies on gender in the areas of education, health, agriculture and vocational and professional training (under the overall guidance of the secretary of state for the promotion of equality).

Significant legislative reform has taken place to harmonise national legislation with CEDAW. Land laws and a civil code have been adopted which grant equal rights to both women and men to use and own land and in all aspects of matrimonial regime and inheritance rights. The criminal code now categorises domestic violence as a public crime, which ensures criminal procedures do not depend upon a formal complaint by the victim. A specific law against domestic violence was recently adopted by parliament. The relationship between formal justice institutions and traditional justice mechanisms, which are most commonly utilised to address domestic violence and sexual violence, may be enhanced through the development of a draft bill on customary law which seeks to ensure that customary practices are consistent with national and international human rights standards, particularly in relation to women and children.

The efforts of the Timorese government, UN entities and civil society to raise the profile of gender issues and put in place gender-sensitive institutional structures and policies have come into sharp relief following the successful election of their nominated candidate, Maria Pires, to the UN CEDAW Committee in June 2010. This was the first victory for Timor-Leste, or one of its nominated candidates, in a UN election; and was the first time Timor-Leste had nominated a candidate for a treaty body. The election was highly competitive with 28 candidates competing for 12 available positions. Pires had served as Country Programme Coordinator for UNIFEM and was a member of the Constituent Assembly that drafted Timor’s constitution. The campaign was closely supported by the gender adviser from UNMIT, who had been specifically placed in UNMIT to assist Timor-Leste in its implementation of and reporting to CEDAW. This adviser is now placed within the Office of the Secretary of State for the Promotion of Equality.

There are several active NGOs working on women’s issues in Timor-Leste. These include the umbrella civil society organisation Redefeto, the head of which addressed the Security Council on the issues facing Timorese women during its debate on women, peace and security in October 2006.

Timor-Leste appointed a woman as permanent representative to the UN in New York for the first time in March 2010.

1325 Project: Liberia/Ireland/Timor-Leste

Liberia, Northern Ireland (supported by Ireland) and Timor-Leste have established a trilateral cross-learning initiative on implementation of resolution 1325. Each partner has hosted information sharing meetings on an aspect of implementing resolution 1325: participation (hosted by Ireland, led by Northern Ireland), protection (Liberia) and prevention (Timor-Leste). The focus of the initiative is to facilitate the sharing of experiences between women in conflict-affected areas and help Ireland and Timor-Leste develop their National Action Plans to implement resolution 1325.

top

8. Cross-Cutting Analysis: Secretary-General’s Reports on Country Situations

Secretary-General’s reports are a key source of information for Council members. Some Council members base their negotiating positions entirely on the information contained in these reports.

In resolution 1325 the Council requested the Secretary-General, where appropriate, to include reporting on gender mainstreaming throughout peacekeeping missions and all other aspects relating to women and girls. In resolution 1820 the Council reinforced this with a request for the Secretary-General systematically to include in his written reports to the Council on conflict situations his observations and recommendations concerning the protection of women and girls from all forms of sexual violence.

Research Methodology

Our analysis is therefore based upon a review of all country-situation reports submitted by the Secretary-General to the Council since the adoption of resolution 1325 to the end of August 2010. We did not include the reports specifically prepared for the working group on children and armed conflict, despite the potential overlap with gender issues. This is because those reports are only handled by the Council’s working group on children and armed conflict and do not explicitly contain the information requested by the Council cited above.

Our analysis is broken down according to the number of reports with a reference to gender issues, and further into those reports with more than one paragraph on gender issues. This is an attempt to gauge the relative depth of references to women and gender issues in Secretary-General’s reports.

Secretary-General’s Reports on Country Situations

2000-2005

From the adoption of resolution 1325 to the end of 2005 the number of references in reports to gender gradually increased from 50 percent of all country-situation reports in 2001 to 86 percent in 2005.

The number of references in reports to gender which contain material greater than one paragraph also increased from around 60 percent in 2001 to closer to 90 percent in 2005.

Over this period we observed an increasing tendency for the Secretary-General to report on gender as a separate section which cuts across missions’ mandates. (Some even have a separate section entitled ‘Implementation of resolution 1325’.) On the other hand, other missions combine gender issues with governance or human rights.

2006-2010

The proportion of Secretary-General’s reports including references to gender issues did not continue to increase in 2007. Moreover it actually dropped to 82 percent in 2008. The proportion increases in 2009 to over 90 percent. It stays at this level for the reports released so far in 2010. The proportion of those with a reference of more than one paragraph peaked at 95 percent in 2009 and has dipped to 85 percent in the first eight months of 2010.

Following the adoption of resolution 1820 there was an increase in reporting specifically on instances of sexual violence and measures being taken by UN missions and host governments to address the issue.

Only one mission includes a separate section on sexual violence—the mission in the DRC.

Analysis

There has been a gradual increase in information on women, peace and security in Secretary-General’s reports, in particular over the past five years. It is now routine to see gender addressed as a cross-cutting issue in a separate section in most reports. This increase can be attributed to a gradual increase in UN activities to implement resolution 1325 in the field, as well as increased calls for information from the Council. Despite such increases, the amount and detail of information in many Secretary-General’s reports still falls short of that requested by the Council. In particular, there has yet to be an increase in detailed information or analysis of the challenges to protecting women from sexual violence in relevant country situations.