Cross-Cutting Report No. 1: Children and Armed Conflict

Cross-Cutting Report in Word format • PDF format

Executive Summary • Methods of Research • Introduction • Evolution of International Standards for Protecting Children in Armed Conflict • From Words to Action : Resolution 1612 and its Tools for the Security Council • Children and Armed Conflict as a Cross-Cutting Issue in the Council: Statistics • Are Children’s Issues Becoming Part of Mainstream Council Activity? Analysis • Assessing the Council’s Tools • Initial Results • The DRC: A Case of Empty Promises? • Council Dynamics • Future Options

The impact of recent conflicts on children has been horrific around the globe. More than two million children have been killed in war zones over the past two decades. Another six million have been maimed or permanently disabled, and more than a quarter of a million youths have been exploited as child soldiers in at least 30 countries. Many of today’s soldiers were recruited as children, without schooling or knowledge of the society around them. Thousands of girls are subject to sexual exploitation, including rape, violence, abductions and prostitution. No region of the world is immune.

Over the last decade, the issue of children and armed conflict has been raised with increasing frequency in the Security Council. In 2005, the Security Council adopted resolution 1612, which authorised the establishment of a monitoring and reporting mechanism at the field level. It also created a Council Working Group on Children and Armed Conflict. Since then, the issue has been firmly on the Council’s agenda.

The issue of children and armed conflict is now taken up in the Council on a systematic basis as a thematic issue. Moreover, the Council has developed tools capable of potentially influencing the country-specific work of the Council. The challenge is ensuring that the thematic work is actually reflected in practice, in a cross-cutting way, in the work of the Council.

This report attempts to gauge whether children and armed conflict has become such a cross-cutting issue by examining the degree to which the issue has been incorporated into the Council’s work on country-specific issues.

It examines Council resolutions, presidential statements and visiting missions; the Secretary-General’s reports; peace agreements; and peacekeeping mission mandates in the period from 2003-2007. It also assesses the impact of the monitoring and reporting mechanism and the Council’s Working Group.

In the main, the report finds that while a Herculean effort has been made to pinpoint abuses, the actual Council response and follow-up in many specific cases is not as effective as might have been hoped. Stronger action, including targeted sanctions, may be needed against persistent violators as well as more systematic procedures to follow up reports and ensure their implementation.

Among the findings:

- The recommendations of the Working Group are increasingly being integrated into the Council’s country-specific resolutions and presidential statements.

- The Working Group has developed working methods and a “tool-kit” to give it flexibility to carry out its mandate on a wide range of actions, but it has had difficulty dealing with violators in conflict situations not on the Council’s agenda.

- The constant spotlight on the issue and the pressure of possible repercussions from the Council have led some governments to agree to action plans to stop recruitment of children.

- Similarly, pressure from the Council has resulted in the release of some child soldiers, such as in Côte d’Ivoire.

- The inclusion of the protection of children in peace agreements and in the Secretary-General’s country-specific reports has been spotty.

- Among Council members, many are reluctant to use strong action in dealing with violators. For example, resolution 1698, adopted on 31 July 2006, called for sanctions against those abusing children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). But no such list of individuals or entities has been drawn up and the Council president conveyed the Working Group’s “grave concern” to the DRC Sanctions Committee about this in January 2008 following up on the Working Group’s recommendations of October 2007.

Other conclusions:

- The development of children and armed conflict as a cross-cutting issue is being driven largely by a small number of members in the Working Group and has yet to be systematically included in country-specific situations.

- The lack of consistency of references to children by the Secretariat in country-specific reports suggests poor coordination between monitors on the ground and the authors of the Secretary-General’s reports at Headquarters.

- The Working Group has concentrated on appeals to parties and letters to governments. It may now have to be more persistent and transparent in following up in the case of persistent violators, although there is reluctance by some Council members to do so.

- There is also a lack of transparency in the follow-up to recommendations made by the Working Group as there is no systematic process in place to assess action taken.

- There appears to be a considerable lag time between conclusions being published by the Working Group and actual action taken.

While the issue of children and armed conflict has been in the Council regularly since at least 1999, this study focuses on a five-year period from 2003 through 2007 and attempts to assess the impact of resolution 1612 and the level of success in mainstreaming children’s issues into the Council’s activities across the range of issues on its agenda.

Information was obtained through research interviews with members of the Working Group on Children and Armed Conflict, the Office of the Secretary-General’s Special Representative (SRSG) for Children and Armed Conflict and non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

Statistical data was obtained from formal documents of the Council, international legal documents and peacekeeping mandates. In analysing Council statistics, an assessment was first made to identify decisions that were “relevant,” i.e. those decisions that could reasonably be expected to include some consideration of children’s protection issues, rather than the total number of Council decisions adopted. As a result, a number of “technical” and other decisions not relevant to children’s issues was excluded from the comparison. In the case of Secretary-General’s reports and peace agreements, because the Council had made a decision that children’s issues should be included in all reports and all peace agreements, our analysis is based on the total number of these reports and agreements.

The number of relevant Council decisions published over the five-year period is relatively small (between 40 and 50 resolutions). This makes it difficult to draw accurate statistical conclusions. As a result, the study uses the numerical data to establish possible patterns in highlighting children and armed conflict in the work of the Council.

Our report also does not attempt to delve into the success of the monitoring and reporting mechanism on the ground. Several NGOs with extensive field experience are involved in researching this issue and are publishing significant new reports. It did not seem sensible to try to duplicate that effort.

top

3.1 Background

In the late 1990s, it had become clear that the impact of armed conflict on children was not just a humanitarian problem but a significant peace and security issue. The face of war had changed. Many conflicts involved armed groups within national boundaries leading to high civilian casualties, particularly among women and children. Moreover, children were being used as a potent instrument of war by both rebel groups and national armies.

In the light of these developments, the Council started to pay sustained attention to the issue of children in war zones. Members expressed concern about the huge rise in the numbers of displaced families and communities, refugee flows across borders and the use of child soldiers – conditions conducive to long-term regional and international instability. The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) puts children at half the total population of refugees and internally displaced people.

The protection of war-affected children was first spotlighted at the World Summit for Children in 1990. In the follow-up to the World Summit, the General Assembly debates on children and armed conflict continued to draw international attention to the fate of children in war-torn areas.

In 1993, the General Assembly asked the Secretary-General to undertake a study of the impact of armed conflict on children. He appointed Graça Machel, a former Minister of Education in Mozambique, to conduct it. Her 1996 report, Impact of Armed Conflict on Children, laid the foundation for a comprehensive international agenda for action. Among her recommendations was that:

“The Council should be kept continually and fully aware of humanitarian concerns, including child-specific concerns in its actions to resolve conflicts, to keep or to enforce peace or to implement peace agreements.” (A/51/306, para.282)

The Machel report led to the creation of the post of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Children and Armed Conflict and the appointment in September 1997 of Olara Otunnu as the first executive. In June 1998, he was invited to brief the Security Council in what was the Council’s first open debate on the subject. The debate gave rise to the first Council decision on the issue, a presidential statement adopted on 29 June 1998, which placed this issue squarely on the international security agenda.

Since 1999, the Council has been actively seized of this issue. In recent years the topic has emerged as the most developed and innovative of the thematic issues. Regular Council debates are held, six resolutions have been adopted and a working group and monitoring and reporting mechanism have been created to provide regular country-specific reports and recommendations.

top

3.2 Security Council Resolutions on Children and Armed Conflict

The first two resolutions, 1261 of 1999 and 1314 of 2000, identified areas of concern such as the protection of children from sexual abuse; the linkage between small-arms proliferation and armed conflict; and the inclusion of children in disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR) initiatives. At this early stage, the resolutions contained essentially generic statements and had a limited impact.

From 2001 onwards the resolutions included concrete provisions. One of the most groundbreaking and controversial was the request in resolution 1379 of November 2001 for the Secretary-General to attach to his report:

“a list of parties to armed conflict that recruit or use children in violation of international obligations in situations which were already on the Council’s agenda or could be brought to its attention as a matter which in his opinion may threaten the maintenance of international peace and security, in accordance with Article 99 of the Charter.”

Nevertheless, there was little evidence on the ground that these measures were successful in getting armed groups and governments to comply. As a result, the Council in 2003 endorsed in resolution 1460, the Secretary-General’s call to move into an “era of application.” The Secretary-General was asked:

- to report on the progress made by parties in stopping the recruitment or use of children in armed conflict;

- to develop specific proposals for monitoring and reporting on the application of international norms on children and armed conflict; and

- to include protection of children in armed conflict as a specific aspect of all his country-specific reports.

A further decision in 2004, in resolution 1539, requested that the Secretary-General “devise urgently” an action plan for a comprehensive monitoring and reporting mechanism that could provide accurate and timely information on grave violations against children in war zones. The resolution asked for parties listed in the Secretary-General’s reports to prepare concrete plans to stop the recruitment and use of children in armed conflicts.

A major breakthrough came the following year in resolution 1612 in 2005, which established the monitoring and reporting mechanism and the Council Working Group on CAC. The Council agreed to set up a mechanism to report on killings, abduction, abuse and sexual exploitation of children in armed conflicts, the recruiting of child soldiers and attacks on schools and hospitals. The resolution was partly a response to the lack of accurate information and action plans requested in resolution 1539 and aimed at stopping the use of child soldiers and the exploitation of children in war zones by governments and insurgent armed groups.

Negotiations, led by France and Benin, took months with many states wary about targeting individual countries. The resolution also reaffirmed the Council’s intention to consider imposing targeted sanctions, including arms embargoes, travel bans and financial restrictions, against parties that continued to violate international law relating to children in armed conflict.

top

3.3 Secretary-General’s Reports on Children and Armed Conflict

The Secretary-General’s reports have played a key role in the conceptual development of this issue in partnership with the Council. The early reports began by documenting the problem and describing situations where children were affected by armed conflict. But beginning in 2002, the reports of the Secretary-General began to call for a strengthened framework and a move towards action. This sought to address the lack of real progress in stopping groups from recruiting and using children in armed conflict. In 2003, the Secretary-General’s call for an “era of application” was endorsed by the Council in resolution 1460. This was the first step towards a system that could better afford a degree of accountability for those committing crimes against children.

A controversial aspect of the Secretary-General’s reports had been the proposal for “naming and shaming” annexes, lists of parties to armed conflict that recruit or use children in violation of international obligations. The Council accepted the challenge and in 2001, in resolution 1379, requested the Secretary-General to create two sets of lists: one for situations on the Council’s agenda, and one for situations that could be brought to the attention of the Security Council by the Secretary-General in accordance with Article 99 of the UN Charter. (The latter provision allows the Secretary-General to refer to the Council a situation that may threaten international peace and security.) Having a list identified by the Secretary-General and endorsed by the Council that actually named parties was a significant step. It was the first step towards putting pressure on those concerned to stop abusing children, or at minimum, devising plans to reach this goal.

In 2002, the Secretary-General provided the first list of parties involved in recruiting and using children in armed conflict. It was a relatively conservative list and attached only an annex of parties involved in conflict situations that were already on the agenda of the Council. However, in his next three reports he included two separate annexes.

In 2005, Annex I listed parties in the following countries on the agenda of the Council:

- Burundi

- Côte d’Ivoire

- Democratic Republic of Congo

- Somalia

- Sudan.

In 2006, the Secretary-General’s Annex I list did not change except to bring Myanmar in as it had been placed on the Council’s formal agenda in September 2006.

In the 2008 report, Annex I parties come from Afghanistan, Burundi, the Central African Republic (CAR), DRC, Myanmar, Nepal, Somalia, Southern Sudan and Darfur.

Annex II, in 2005, listed the following parties in situations not on the Council’s agenda:

- Colombia

- Myanmar

- Nepal

- The Philippines

- Sri Lanka

- Uganda.

In the 2006 Secretary-General’s report, Chad was added to Annex II. The 2008 report lists the following parties under Annex II: Chad, Colombia, the Philippines, Sri Lanka and Uganda.

Annex II has been a source of contention among member states ever since it first appeared in the Secretary-General’s report in 2003. States listed in Annex II were concerned that once a situation was considered by the Council, it was but a short step away from being placed on the body’s formal agenda.

top

4. Evolution of International Standards for Protecting Children in Armed Conflict

The increased political focus on children and armed conflict has gone hand in hand with the evolution of legal instruments based on humanitarian and human rights law. Among the most significant are:

- The 1977 Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions for the first time addressed, in a binding international document, the recruitment and deployment of children.

- The Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, adopted in May 2000 by the General Assembly, raised the minimum age from 15 to 18 for direct participation in national forces and prohibited compulsory recruitment for under-18s into national armed forces. (It did not prohibit voluntary recruitment by states for under-18s.) The Protocol forbids non-state armed groups both from recruiting and using persons under 18.

- The Rome Statute for the International Criminal Court, adopted in July 1998 by 120 governments, classified the conscription, enlistment or use of children under the age of 15 in hostilities as a war crime ;

- The Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention (Convention 182) of the International Labour Organisation (ILO), adopted in June 1999, focused on the elimination of the worst forms of child labour, including the forced recruitment of children under 18 for use in armed conflict. In February 2007, the Paris Commitments/Paris Principles and Guidelines on Children Associated with Armed Forces or Armed Groups were signed by 57 states. The 2007 “Machel 10 Year Strategic Review” marks the 10-year anniversary of the Graça Machel’s study on the impact of armed conflict on children. These documents point to a determination to continue to build international standards for the protection of children.

The Paris Commitments/Principles are a set of guidelines on the disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration of all categories of children associated with armed groups. The initial findings of the Machel strategic review report were published in the 13 August 2007 report of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict to the General Assembly and the final report is expected to come out in April 2008.

5. From Words to Action: Resolution 1612 and its Tools for the Security Council

5.1 The Monitoring and Reporting Mechanism

Resolution 1612 created procedural structures for the implementation of that resolution:

- a monitoring and reporting mechanism at the country level on grave child rights violations; and

- a Council Working Group on Children and Armed Conflict.

On the monitoring and reporting mechanism, resolution 1612 stated:

“the mechanism is to collect and provide timely, objective, accurate and reliable information on the recruitment and use of child soldiers in violation of applicable international law…and that the mechanism will report to the working group…”

Resolution 1612 provided information on the scope of the Working Group’s activities but left open details on the methods to carry out its mandate. This necessitated innovation by the group’s members.

The monitoring and reporting mechanism includes a procedure for collecting data from the field, organising and verifying information on violations against children in armed conflict and monitoring progress being made on the ground in complying with international norms on children and armed conflict.

The monitoring and reporting mechanism has now been established in most of the situations of armed conflict listed in the Annex I of the Secretary-General’s report, i.e. Burundi, Côte d’Ivoire, the DRC, Nepal, Somalia and Sudan. Two nations in Annex II, Sri Lanka and Uganda, have voluntarily agreed to set up a monitoring and reporting mechanism. Myanmar and the Philippines seem to be open to cooperation. Colombia has yet to respond positively.At the field level, the monitoring and reporting mechanism includes UN agencies (The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO), the UN Development Programme (UNDP)), as well as NGOs and other civil society groups. These entities compile information at the country level. Their data forms a report from the Secretary-General to the Council’s Working Group after an internal review by the Office of the Special Representative for Children and Armed Conflict and UNICEF.

In the last two years, the monitoring and reporting mechanism has provided a reliable and consistent flow of information on six categories of violations against children. They are:

- recruiting and use of child soldiers;

- killing and maiming of children;

- rape and other grave sexual violence against children;

- illicit exploitation of natural resources;

- abduction of children; and

- denial of humanitarian access to children.

5.2 The Security Council Working Group on Children and Armed Conflict

The Working Group was established by the Council to review the reports of the monitoring and reporting mechanism and to assess progress in the development and implementation of the action plans by entities listed in the Secretary-General’s “name and shame” lists. The Working Group can also make recommendations on the protection of children affected by armed conflict and can work with other bodies in the UN system to support the implementation of resolution 1612.

After its establishment on 16 November 2005, the Working Group spent much of its first year adopting decisions needed to carry out its mandate and to implement the monitoring and reporting mechanism. France was chosen as the chair, breaking a Council tradition that usually excluded permanent members from heading subsidiary bodies.

The Working Group adopted its terms of reference followed by a provisional programme of work and guidelines for submission of reports by the Secretary-General. (The terms of reference are contained in S/2006/275, but the two other documents were not published.)

In June 2006, the Working Group considered the Secretary-General’s first report to it – on children and armed conflict in the DRC. The Working Group has met every two or three months to consider further reports from the Secretary-General on children and armed conflict in specific country situations. The Working Group also reviews a bimonthly “horizontal note” from the Secretariat on other situations of concern or updates since the last reporting period. The Working Group in 2006 and 2007 published its conclusions at regular intervals. (However, conclusions on Côte d’Ivoire and Chad, considered in October 2007, have taken longer to be released and have not yet been published.)

By the end of 2007, the Working Group had held 11 meetings and moved into the second round of reporting for the DRC, Sudan, Côte d’Ivoire and Burundi. The first reports on the Philippines and Colombia have yet to be considered.

The Working Group’s methods (described in more detail in the section on “Assessing the Tools” below) have given it the unusual flexibility to carry out its mandate and overcome differences among Council members.

5.3 The Office of the Special Representative on Children and Armed Conflict

A key actor in the implementation process of resolution 1612 is the Secretary-General’s Special Representative (SRSG) on Children and Armed conflict. The Office of the SRSG plays a central role in managing the smooth flow of information between the UN bodies on the ground and Headquarters. Over time it has also begun to work closely with both members of the Working Group on Children and Armed Conflict and governments. The position of SRSG on Children and Armed Conflict, however, happened to be vacant shortly after the adoption of resolution 1612 (Otunnu left the post in 2005) and was unfilled for seven months, perhaps one reason for delays in implementing the measure. The new SRSG, Radhika Coomaraswamy, was appointed in February 2006 and took office in April that year.

An important aspect of the SRSG’s strategy has been field visits to situations of conflict where children are involved. Her visits have proven valuable in supporting UN field officers, stimulating the preparation of action plans and engaging NGOs and civil society groups.

Over the last two years, the SRSG has visited Sudan, Burundi, the DRC, the Middle East (Lebanon, Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories), Sri Lanka (conducted by the SRSG’s Special Advisor) and Myanmar. Before resolution 1612, field visits yielded meagre results. However, since its adoption, these visits have led to commitments to action plans and other promises by parties to a conflict. It appears that the Council’s increased attention to this issue has triggered a deterrent that the SRSG can use in dealing with parties involved.

6. Children and Armed Conflict as a Cross-Cutting Issue in the Council: Statistics

In coming up with this data we used the following guidelines:

- In examining resolutions and presidential statements, an assessment was made of decisions that were relevant, i.e. those decisions that could reasonably be expected to include some consideration of children’s protection issues rather than the total number of Council decisions issued. A number of “technical” and other decisions not relevant to children’s issues have been excluded, such as resolutions rolling-over a mission’s mandate for a short period or decisions on non-proliferation and international tribunals.

- For the Secretary-General’s reports and peacekeeping mandates, we used the total number of reports and mandates for the period examined as there had been decisions to include children’s issues in all reports and peacekeeping mandates.

- Given the small number of thematic resolutions and presidential statements and mission reports each year, we did not make a distinction between decisions that could be expected to include children’s protection issues and the others.

A judgement was also made of the quality of the references to children. Only if references to children were deemed substantive and relevant to the issue of children and armed conflict were they included. For example, documents which included the feeding of children by the World Food Programme, although an important activity, were not taken as significant to the issue of children and armed conflict.

6.1 Resolutions

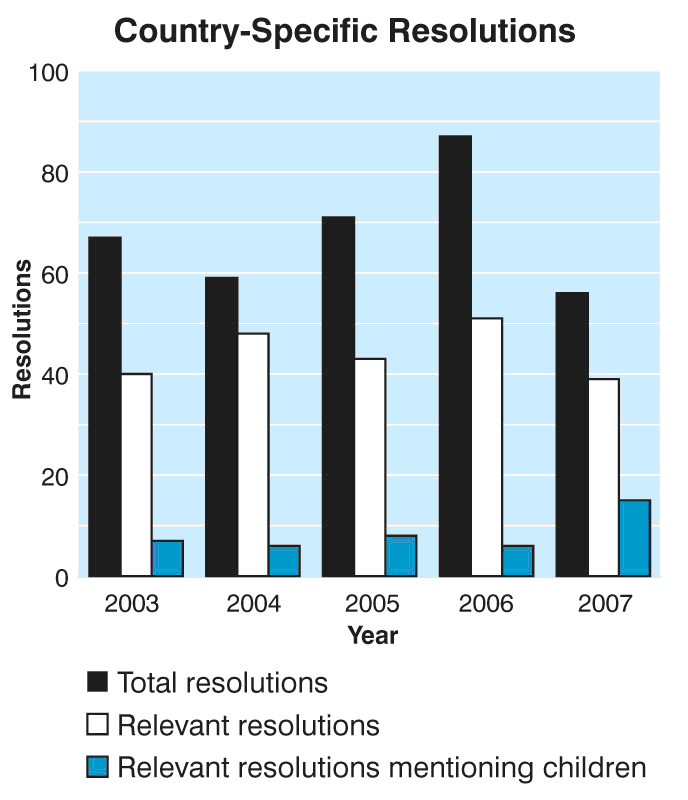

ctual references in the Council decisions to children were between six and eight. In 2007 a large increase in the number of resolutions with references to children is observed. There were 38 relevant resolutions and 15 with references to children, representing a 50 per cent increase over the previous four years.

Chart 1: Country-Specific Resolutions

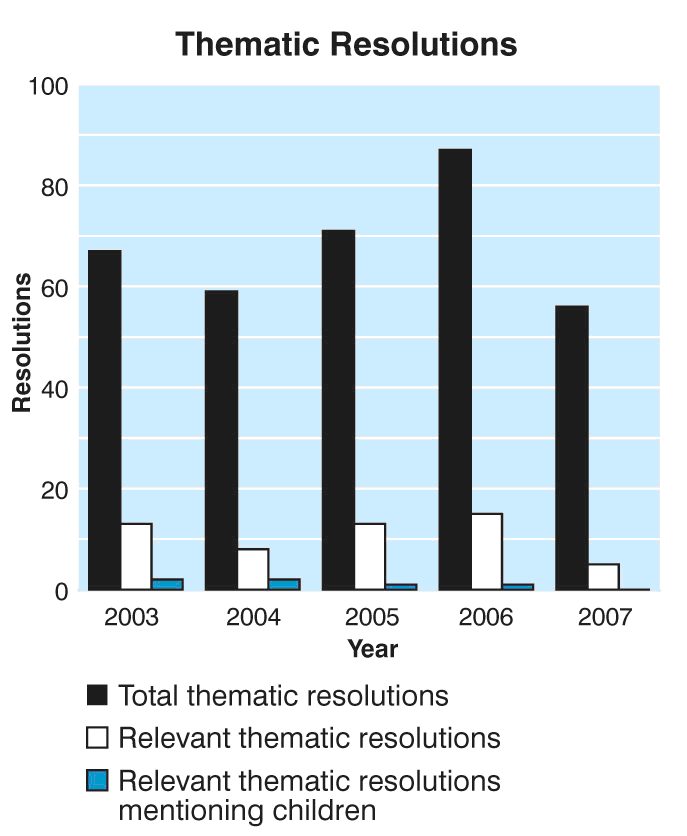

The overall number of thematic resolutions varied between 5 and 15 per year in the years 2003 to 2007. Thematic resolutions with references to children varied from zero to two. In 2007, there were no references, but all the thematic resolutions that year were on issues such as international tribunals, non-proliferation and terrorism, which are less likely to contain children’s issues.

Chart 2: Thematic Resolutions

6.2 Presidential Statements

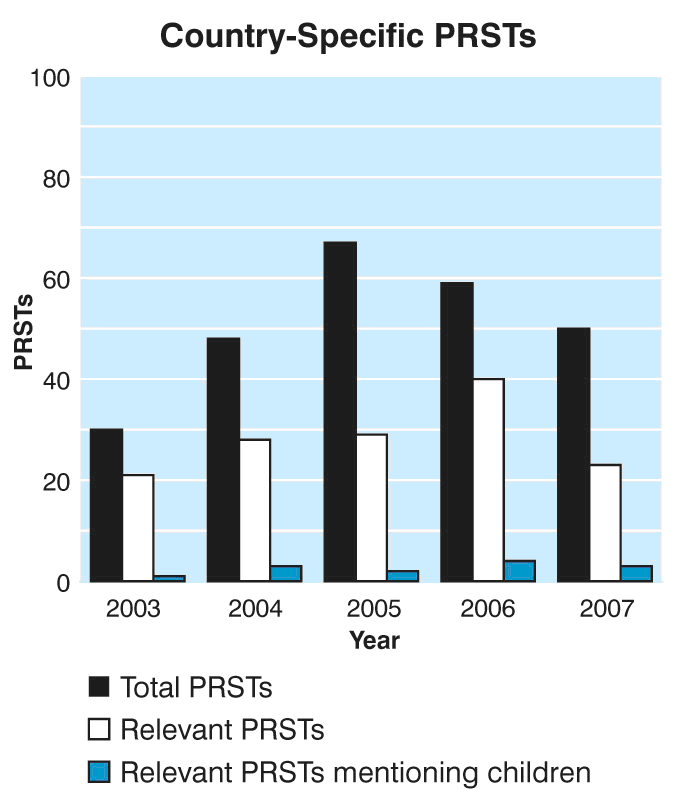

From 2003 through 2007, the number of relevant country-specific presidential statements (PRSTs) (i.e. those that we assess to have potential relevance to children and armed conflict) varied between 20 and 40. Those that contained substantive mention of children’s issues varied between 1 and 4. In 2006, there was an unusually high number of relevant PRSTs, but only four mentioned children.

Chart 3: Country-Specific Presidential Statements

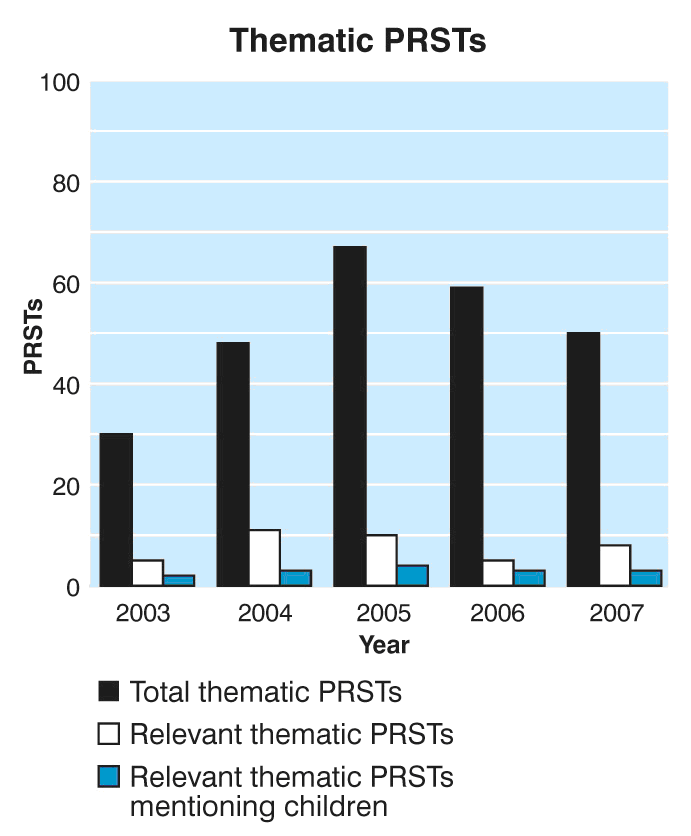

The number of thematic PRSTs between 2003 and 2007 ranged from 5 to 10 with 3 to 4 containing issues relevant to children and armed conflict.

Chart 4: Thematic Presidential Statements

6.3 Secretary-General’s Reports

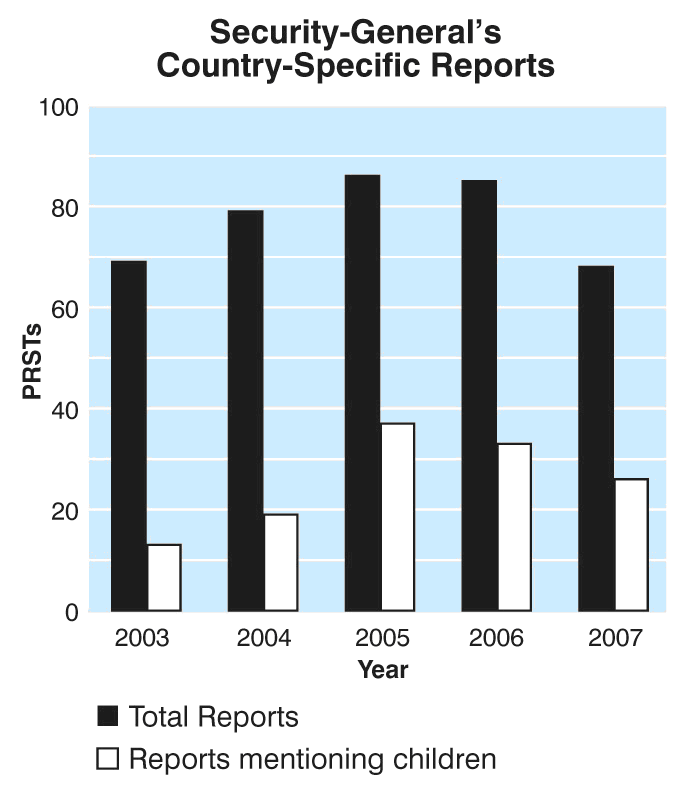

There was an increase in references to children in Secretary-General’s country-specific reports from 2003 through 2005. In 2003, 18% of the reports contained references while in 2005 it was 43%. However, substantive references to children were only found in 38% of Secretary-General’s reports in 2006 and 2007.

Chart 5: Secretary-General’s Country-Specific Reports

6.4 Security Council Mission Reports

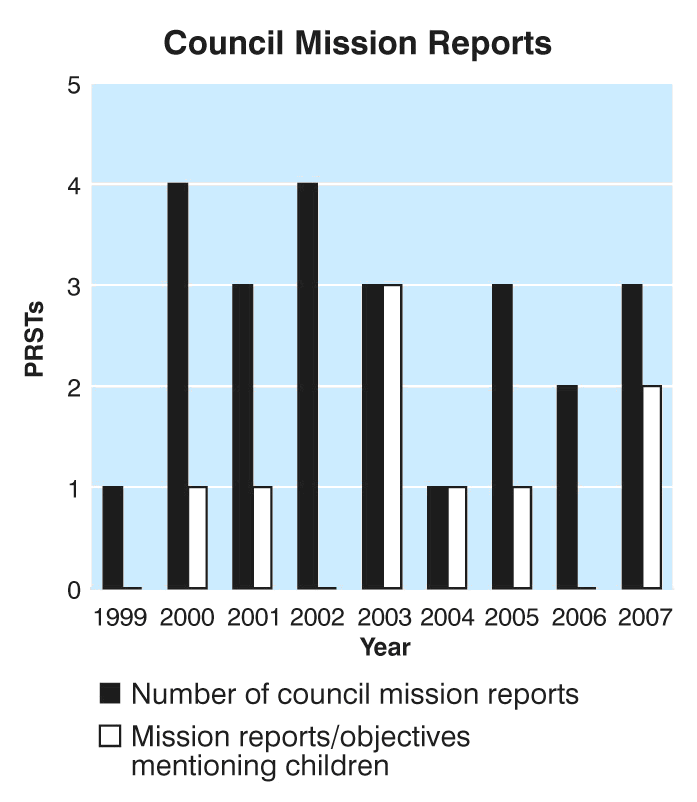

The Council went on 27 missions between 1999 and 2007. Only nine of its mission reports indicated a focus on children’s issues.

Chart 6: Council Mission Reports

6.5 Peace Agreements

An examination of peace agreements from 1999 – 2007 showed that only a small number include a focus on protection of children. Of the 30 related to issues under Council consideration, only 6 made any reference to protection of children. (See Annex).

6.6 Peacekeeping Missions

Starting with resolution 1379 in 2001, the Council requested the protection of children be taken into account in peacekeeping proposals submitted to the Council by including posts for child protection staff in such operations. This was reiterated in resolution 1460 of 2003 and again in resolution 1539 of 2004 and 1612 of 2005.

Of the nine peacekeeping operations set up between 1999 and 2007, the mandates of all except the UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea (UNMEE) referred to children in relation to human rights or disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR).

|

Peacekeeping Mission |

Date Established |

Reference to Children in Mandate |

|

(MINURCAT) CAR and Chad |

25 September 2007 |

Yes |

|

(UNAMID) African Hybrid Operation for Darfur, Sudan |

31 July 2007 |

Yes |

|

UNMIN (Nepal) |

23 January 2007 |

Yes |

|

UNMIT (Timor-Leste) |

25 August 2006 |

Yes |

|

UNIOSIL (Sierra Leone) |

31 August 2005 |

Yes |

|

UNMIS (Sudan) |

24 March 2005 |

Yes |

|

UNOCI (Côte d’Ivoire) |

27 February 2004 |

Yes |

|

ONUB (Burundi) |

21 May 2004 |

Yes |

|

MINUSTAH (Haiti) |

30 April 2004 |

Yes |

|

UNMIL (Liberia) |

19 September 2003 |

Yes |

|

MINUCI (Côte d’Ivoire) |

13 May 2003 |

Yes |

|

UNMEE (Ethiopia-Eritrea) |

15 September 2000 |

No |

|

MONUC (DRC) |

24 February 2000 |

Yes |

7. Are Children’s Issues Becoming Part of Mainstream Council Activity?: Analysis

7.1 Resolutions

An analysis of references to children in resolutions from 2003 – 2007 indicated:

- A spike in references to resolution 1460 (2003) and resolution 1539 (2004) in the twelve–month period after their adoption. 57 percent of relevant resolutions mentioned resolution 1460, and 62 percent of relevant resolutions cited resolution 1539.

- A decline in the overall number of references to children after resolution 1612. In the twelve-month period after the July 2005 adoption of resolution 1612, there were only four resolutions referring to children and just one on Sudan made a specific reference to the resolution.

- From July 2006 on, references became more frequent, including more specific references to resolution 1612 and the Working Group.

While the exact reasons are difficult to pinpoint, two key factors seem likely to have contributed to the drop in references to children in the Council’s resolutions immediately after resolution 1612 was adopted:

- the battle to get consensus on the resolution exhausted many Council members, who were then willing to let the Working Group handle the issue; and

- the Working Group took almost a year to set up and consider its first report. During this time there appears to have been little energy left over for cross-cutting analysis of the Council’s agenda, whether on country-specific issues or thematic topics.

However, in 2006, two resolutions – on the UN Integrated Mission in Timor-Leste (UNMIT) (S/RES/1704) and the UN Integrated Office in Burundi (BINUB) (S/RES/1719)—contained references to the protection of children, indicating a need to include such concerns in peacekeeping mandates. The same is true for the resolution expanding the mandate of United Nations Mission in Sudan (UNMIS), which called for the development and implementation of a programme for disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration of children formerly associated with combatants (S/RES/1706).

There are also references to children in resolutions on Haiti, especially in 1780 of October 2007, when the Security Council “condemned strongly the grave violations against children affected by armed violence, as well as widespread rape and the sexual abuse of girls”. (Haiti has never been on the annexes of the Secretary-General’s report on children and armed conflict but is included in the main body.) The Secretary-General’s 2006 report on children and armed conflict reported widespread and systematic violence against girls by criminal gangs in Haiti and estimated that up to 50 percent of girls living in conflict zones had been victims of sexual abuse. And it faulted the National Haitian Police for illegal detention and sexual molestation of girls in custody as well as the reports of execution and mutilation of street children.

In May 2004 when the UN Stabilisation Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) was set up in resolution 1542, its mandate included DDR programmes for children associated with armed groups.

It seems that part of the reason for the relatively low number of references to children in thematic resolutions is that every year a number of resolutions considered “thematic” relate to areas such as international tribunals and terrorism sanctions on Al-Qaida or specific terrorist attacks. Among the thematic resolutions that might have been expected to contain references to children were two on protection of civilians in 2006, one on regional organisations in 2005 and a resolution on prevention of armed conflict in Africa issued after the Council summit in 2005.

Overall, the issue of children and armed conflict has grown in significance. One finding in examining Council resolutions between 2003 and 2007 is that a practice has developed of inserting specific references to the conclusions of the Working Group when the Council adopts decisions on situations covered by the Working Group on Children and Armed Conflict. Council resolutions in 2007 included references to the Working Group’s conclusions regarding the DRC, Sudan, Chad, Burundi, Somalia and Cote d’Ivoire. But it is too early to judge their impact on the ground.

Interviews with members of the Working Group show that this has taken place as a result of ad hoc cooperation between members of the Group and those drafting country-specific resolutions. As such, the practice has not evolved into a coherent strategy, but positive feedback to the initial efforts to include references to the conclusions of the Working Group in these resolutions may encourage more significant references in the future.

7.2 Presidential Statements

The number of PRSTs mentioning children has remained consistently low over the years, never rising above 10 percent. However, the quality of the content has improved. Before 2007, the PRSTs contained general references to the needs and protection of women and children. But in 2007, more specific references to children and armed conflict were made in two of three relevant PRSTs. The statement on 22 March (S/PRST/2007/6) made reference to resolution 1612 in urging the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) to release all women, children and other non-combatants. And the presidential statement on 30 May on Burundi (S/PRST/200716) referred to the February 2007 conclusions of the Working Group on the situation in Burundi and called on the government of Burundi and the UN agencies and donors to cooperate with the Working Group. This included an appeal by the Working Group to the government of Burundi to address the demobilisation of child soldiers in the implementation of the Comprehensive Ceasefire Agreement and to donors for support for the implementation of DDR programmes.

It is perhaps not surprising that the protection of children is rarely mentioned in thematic PRSTs as many are not relevant to the issue. Exceptions are the Protection of Civilians, Women, Peace and Security and Children and Armed Conflict as well as the PRSTs on cross-border issues in West Africa, which regularly mention the special needs of child soldiers.

The absence of children’s issues was evident in a series of presidential statements in 2005 on the role of the Council in UN Peacekeeping Operations (S/PRST/2005/20 of 26 May), Humanitarian Crisis (S/PRST/2005/30 of 12 July), and Women, Peace and Security (S/PRST/2005/52 of 27 October). This absence is also noted in statements on regional organisations. Out of three presidential statements on regional organisations issued over the five-year period, none contained references to the importance of regional organisations also addressing the problems of children and armed conflict. Presidential statements on small arms were not consistent in their references to children. The two thematic PRSTs on small arms in 2004 and 2007 (S/PRST/2007/24 and S/PRST/2004/1) did not mention children. However, in 2005 the small arms PRST referred to the special needs of child soldiers and women (S/PRST/2005/8).

Overall, it can be said that the number of references to child protection has not increased significantly over the last five years. However, the inclusion of more specific references in 2007 shows the potential for using the Working Group’s reports in a cross-cutting approach to the Council’s agenda.

7.3 Secretary-General’s Reports

The first three resolutions on children and armed conflict adopted between 1999 and 2001 requested that the Secretary-General include in his reports recommendations for the protection, welfare and rights of children when “taking action aimed at promoting peace and security” (S/RES/1261, S/RES/1379 and S/RES/1314). In 2003, resolution 1460 requested that the Secretary-General ensure that all his reports to the Security Council on country-specific situations include the issue of the protection of children.

The overall percentage of reports containing any reference to the protection of children, whether humanitarian concerns or child soldier recruitment, has increased over the years and doubled between 2003 and 2005. However, a large number of reports pay no attention to this issue. In 2006 and 2007, only 38 percent included references to children despite the Council’s instructions.

In terms of substance, the references that have been made to children have become more relevant to armed conflicts. For example, in 2007 all the Secretary-General’s country-specific reports on issues covered by the Working Group on Children and Armed Conflict included references to children.

Although sections devoted to child protection appeared in reports more frequently from 2005 onwards, this is not a standard feature. Rarely does the protection of children in armed conflict appear in the Secretary-General’s recommendations for a country-specific situation unless it is also covered by the Working Group. And among those reports, few refer to that body’s conclusions. (This contrasts with the fact that reports and conclusions of the Working Group were mentioned in all 2007 country-specific resolutions in situations covered by the Working Group.) While the Working Group has influence over Council resolutions, there appears to be few advocates in the Secretariat. In this respect, it seems that commitment to implementation is much more highly developed in the Council than in the Secretariat. A possible explanation for this is that members of the Working Group, particularly France, have played an active role in ensuring that references to the conclusions of the Working Group on children and armed conflict are included in relevant resolutions. However, they have less influence over the Secretary-General’s reports.

Another pattern seen in the Secretary-General’s reports is that child protection references are more common in reports covering volatile recent conflict situations such as Sudan, the DRC and Cote d’Ivoire. In contrast reports on Ethiopia and Eritrea, Georgia, Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina rarely include sections on protection of children. The kind of proactive preventive approach envisaged in resolution 1460 seems to be missing.

7.4 Security Council Mission Reports

Before 2000, none of the terms of reference or reports of Council missions included children’s issues. Since 2000, such references have been inconsistent. Worth noting is the fact that in 2007, the mission to Cote d’Ivoire encouraged Ivorian parties to the Ouagadougou Agreement to ensure protection of vulnerable citizens, in particular women and children. And the Timor-Leste mission report in 2007 referred to police insensitivity to incidents in the camps for internally displaced persons where women and children were victims of violence. But there does not appear to be a concerted effort for Council missions to examine issues of children and armed conflict on the ground.

7.5 Peace Agreements

Starting in 2001 with resolution 1379, Council resolutions on children and armed conflict stressed that protection of children needs to be factored into peace agreements, including provisions relating to disarmament, demobilisation, reintegration and rehabilitation. Since then, nearly all Council resolutions on children and armed conflict have called upon parties to conflicts to ensure that protection and rights of children were integrated into “peace processes, peace agreements and the post-conflict recovery and reconstruction phases”.

But compliance has been poor (See Annex.)

The low numbers may reflect the fact that, in practice, the Council does not systematically follow up closely its negotiations of peace agreements – or follow up on its thematic resolutions.

Peace accords that do contain references to children include:

- the 1999 Lome Peace Accord on Sierra Leone;

- the 2000 Arusha Accords on Burundi;

- the 2003 the Accra Peace Agreement on Liberia;

- the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement on Sudan;

- the 2006 Darfur Peace Agreement; and

- the 2006 Comprehensive Peace Agreement in Nepal.

The Comprehensive Peace Agreement, which in 2005 officially ended decades of civil war in Sudan, required the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A) and the Government of Sudan to commit to child demobilisation throughout the country.

The ill-fated Darfur Peace Agreement (DPA) in 2006, while it did not secure peace, did stress the protection of women and children, an apparent response to the worldwide outcry over massacres, rape and abuse of civilians in Sudan’s western region. The DPA called for the release of all boys and girls associated with armed forces and groups. It also paid particular attention to the protection of children in camps as well as reintegration issues.

7.6 Peacekeeping Missions

All the mandates for peacekeeping missions established since 1999 include some form of protection of children, usually under a section on human rights or humanitarian concerns.

Recent peacekeeping mission mandates have paid more attention to children and armed conflict. The July 2007 resolution (S/RES/1769) on the creation of an African Union/UN hybrid peacekeeping mission in Darfur (UNAMID) specifically requested that protection of children be addressed in implementing any Darfur peace accord and asked for continued monitoring and reporting on grave violations against children. The September 2007 resolution on Chad and the Central African Republic mission (MINURCAT) called for the UN operation to strengthen the government’s capacity to put an end to recruitment and use of children by armed groups.

An important outcome of the high-level focus on children in war zones is the deployment of child protection advisors in peacekeeping missions. Resolution 1261 (1999) requested the Secretary-General to ensure “personnel involved in United Nations peacemaking, peacekeeping and peace-building activities have appropriate training on the protection, rights and welfare of children.” The first Child Protection Advisor (CPA) was sent to the United Nations Assistance Mission in Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL) in 2000. Since then, Child Protection Advisors have been deployed in seven other peacekeeping operations: Haiti, the DRC, Burundi, Angola, Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia and southern Sudan. As of January 2007, some 60 CPA posts had been filled in six missions, with the largest number in Sudan and the DRC.

top

8. Assessing the Council’s Tools

8.1 The Working Group on Children and Armed Conflict

Children and armed conflict is unique as a thematic issue because of a dedicated working group to follow up thematic issues in a cross-cutting way. Resolution 1612 is not specific about how the working group and monitoring and reporting mechanism should work. As a result, members were not bound by strict guidelines. They developed working methods that include:

- inviting non-Council members to discussions;

- publishing a document referred to as the tool-kit used to evaluate violators and develop conclusions on situations of children involved in armed conflict; and

- setting up a follow-up procedure at the country level.

The procedures of the Working Group evolved through experimentation by its members. Non-Council members were invited to meetings to provide feedback to reports affecting their respective countries. They were originally meant to comment and leave but soon found themselves drawn into active discussions. The transparency of this practice has helped quell concerns that the Working Group would overstep its bounds. So far only one permanent representative, from Somalia, has turned down an invitation to attend a Working Group’s meeting, but he later provided written comments.

The Working Group follows a work programme adopted at the start of each year. This has remained a confidential document, possibly to provide flexibility in being able to adapt if some reports are not ready on time. (However, earlier knowledge of the timing of the different reports would be helpful to NGOs and other actors in preparing their own complementary work.)

Another area that could be improved is the follow-up to the Working Group’s conclusions. The Working Group’s chair is empowered to follow-up conclusions and regularly does so with letters, demarches and informal contacts. But neither the Working Group nor the Secretariat has the capacity or a system in place yet which is able to systematically determine whether recommended action has been implemented. In addition, the letters from the chair of the Working Group and the president of the Council are rarely published, making it difficult for others to trace the action taken. Putting in place a more systematic procedure would allow for easier review of the Group’s proposals.

8.2 A Flexible Tool-Kit

The “tool-kit”, a document containing the range of possible actions in response to violations, was published on 11 September 2006 (S/2006/724). It has been used as the basis for the Working Group’s conclusions to all the reports examined so far.

While the kit provides 26 possible tools, an examination of recommended actions shows not all means at the Working Group’s disposal have been utilised. The actions are divided into the following categories:

- demarches;

- assistance;

- enhanced monitoring;

- improvement of mandates; and

- other measures.

The most commonly used actions are letters and appeals to parties to the conflict, to UN bodies for technical assistance and to donors for contributions.

However, a number of possible actions available to the Working Group have never been proposed. Among them are field trips by the Working Group followed by a report, demarches to draw attention to the full range of justice and reconciliation mechanisms or a request for a specific resolution or presidential statement. But getting consensus on action, particularly on situations not on the Council’s agenda, has often proved tricky. Suggestions that targeted sanctions or references to the ICC be used have been met with resistance. It appears that the Working Group has sometimes taken the path of least resistance and focused on more limited measures, such as letters to parties involved in recruiting children. Only in two cases, the DRC and Cote d’Ivoire, did the Working Group hint at targeted measures.

Still, in June 2007 the Working Group used a new tool – public statements – which could be issued from either the chair of the Working Group or the president of the Council. This has been an innovative way of handling situations that are not on the Council’s agenda, such as Sri Lanka. The chair of the Working Group was able to address nonstate actors involved in recruiting children such as the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Ealam (LTTE) and the Karuna group through a public statement, hinting at a possibility of stronger action in the future.

The chair of the Working Group has also used press statements and addressed the media following Working Group meetings. These statements were published on the French mission’s website, beginning in November 2005 when the Working Group was established. But they disappeared after May 2007.

8.3 The NGO Factor

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have traditionally worked closely with the Council on this issue. Groups like the Watchlist on Children and Armed Conflict, Save the Children and the Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers have been instrumental in developing this issue. With the existence of the monitoring and reporting mechanism, NGOs also have a chance to contribute information more directly. In New York, the Office of the Special Representative on Children and Armed Conflict conducts regular briefings and is open to feedback from NGOs.

NGO input is also obtained through broader, informal meetings, known as the “Arria Formula,” initiated in 1992 by then Venezuelan ambassador Diego Arria. Since 2000 Arria Formula meetings have been held before every open debate on children and armed conflict. And affected children themselves have addressed public meetings. In 2000, a former child soldier became the first to speak to the Council. He was followed in 2001 by the presentation of three children in an open debate on children and armed conflict. In July 2007, France, as chair of the Working Group, hosted an Arria meeting for NGOs before the publication of the Secretary-General’s second report on children and armed conflict in the DRC.

In response to the UN agenda, groups such as Human Rights Watch and Watchlist on Children and Armed Conflict have timed their reports with Working Group discussions. (Human Rights Watch last year issued related reports on Sri Lanka, Nepal and Chad, while the Watchlist on Children and Armed Conflict launched reports on the DRC in 2006 and Sudan in 2007.)

9. Initial Results

Despite enormous challenges, the Security Council role has begun to see some positive outcomes. In 2004 when the Council in resolution 1539 first called for concrete, time-bound action plans, few responded. Since then, progress is discernable on action plans with armed forces and groups in the Central African Republic, Cote d’Ivoire, Myanmar, Sudan, Sri Lanka and Uganda. The initial results include:

- Central African Republic: the government, the Assembly of the Union of Democratic Forces rebel group and UNICEF signed an agreement in June 2007 for the release and reintegration of some 400 children associated with armed groups.

- Sudan: the (southern) Sudan Liberation Movement Army (SLM/A) agreed on the modalities for the identification and release of children with UNICEF in June 2007.

- Uganda: following the SRSG’s visit in June 2006, the government promised to strengthen implementation of the existing legal and policy frameworks and action plans.

- Chad: the government in May 2007 signed an agreement for the demobilisation of child soldiers from the armed forces throughout the country.

The most positive response is in Côte d’Ivoire where about 1,200 children were released to UNICEF following an agreement in November 2005 by Forces armees des Forces nouvelles (now Force de Defense et de Securite des Forces nouvelles, FDS-FN). In September 2006, four major pro-government militia groups made commitments to identify children in their forces and began releasing 204 of them. All parties have entered into concrete, time-bound action plans and completed the requirements in these plans.

However, Myanmar and Colombia have been reluctant to have the UN engage with nonstate actors, a position that has slowed the development of action plans. In Uganda the action plan has yet to meet international standards.

There have also been promising developments in the use of international legal instruments to fight impunity for the crime of using children in armed conflict.

- The International Criminal Court (ICC) has confirmed charges against Thomas Lubanga of the Union of Congolese Patriots of the DRC, for the conscription and enlistment of children under the age of 15 and the use of children for active participation in hostilities.

- The ICC has also issued arrest warrants for five senior members of the Lord’s Resistance Army, including its leader, Joseph Kony, who is charged with 33 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity, including the forcible enlistment and use of children under 15 in hostilities.

- The Special Court for Sierra Leone convicted and sentenced two members of the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council and one member of the Civil Defence Forces militia for, in addition to other crimes, recruitment and use of child soldiers.

- The Special Court for Sierra Leone is also currently trying Liberia’s former president Charles Taylor for 11 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity, including conscripting and enlisting children into armed forces or groups and using them to participate actively in hostilities.

10. The DRC: A Case of Empty Promises?

Few conflicts before the Council have produced such a continuous flow of heartbreaking testimony as the plight of children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Despite promises of demobilisation and reintegration, resources for far-reaching programmes have been lacking. Instead children have been recruited for exploitation of natural resources and given food in exchange. Many others are child soldiers or sex slaves, raped and abducted. The Secretary-General in his report of 28 June 2007 blamed not only militia and insurgent groups in the volatile eastern part of the country but said Congolese security forces, mainly the army, were responsible for half of the violations.

An estimated four million people, half of them young children, have lost their lives through conflict, disease and malnutrition since the 1998-2003 civil war and its aftermath, according to UNICEF and other reports.

The violence and the recruitment of children into warfare are most severe in the east, where they make up more than a third of the fighting forces. The head of the Congolese military in January ordered the North Kivu brigades to stop recruiting and using children as soldiers, but former rebel warlords integrated into the army have failed to follow this order and children are still on the front lines.

Much hope is pinned on a recent ceasefire pact between the government and warring eastern rebel and militia factions, but details affecting children have yet to emerge.

In July 2006, the Working Group examined the DRC, its first report on children and armed conflict in a country-specific situation. Shortly afterwards, the Council adopted resolution 1698, which for the first time extended sanctions to “political and military leaders recruiting or using children in armed conflict” and individuals committing serious violations of international law involving children in situations of armed conflict. The following year resolution 1771 of 10 August 2007 renewed the sanctions.

But the DRC Sanctions Committee has taken no decision and imposed no punishment on individuals and entities directly involved with abuse of children. In contrast, punitive measures involving violations of an arms embargo or failure to disarm illegal armed groups have been adopted.

Some members say the Group of Experts on the DRC sanctions and the Working Group have not yet supplied enough concrete information on individuals and entities, although the UN Mission in the DRC (MONUC) and the Secretary-General’s reports give a number of examples. It is noteworthy that the Council president, at the request of the Working Group, wrote in January 2008 to the Chair of the Sanctions Committee expressing “grave concern” about “repeated violations” of Council resolutions by named persons (S/AC.51/2008/4)

The new 2008 chair of the DRC Sanctions Committee, Indonesia’s ambassador Marty Natalegawa has informed members that he plans to follow up on the letter from the president of the Council.

The origin of the letter is the Working Group’s conclusions published on 25 October 2007 in which the Group agreed to ask the Council president to inform the DRC Sanctions Committee of its grave concern. It is especially noteworthy that it has taken three months for a letter expressing grave concern to be transmitted and in the interim no action has been taken.

The Working Group also acknowledged in October 2007 the cooperation of the government of the DRC and urged it to address the issue of impunity for those committing crimes against children.

In its report in July 2007, the Group of Experts on the DRC recommended that the Committee engage child protection actors to address issues of protection of children who are acting as witnesses before it considers imposing individual sanctions. There is no indication this has been followed up.

Action against abusers of children seems to have been passed around from one group to another. The DRC Government has arrested one alleged perpetrator, Kyungu Mutanga, who is now before the International Criminal Court on charges of forcibly recruiting child soldiers. The Secretary-General has asked the government to issue arrest warrants against others while at the same time raising concerns about some in the security forces. And the Security Council has delayed any specific sanctions action against the perpetrators.

It is significant to note that in 2004 and 2005 the Council in resolution 1565 and resolution 1649 directed the UN troops to cooperate with Congolese authorities “to ensure that those responsible for serious violations of human rights and international humanitarian law are brought to justice.” However, this authority has not been effectively implemented.

top

11.1. Past Dynamics

The issue of children and armed conflict has divided Council members. Other than France, which has led on the issue from the start, the other permanent members were reluctant at the outset.

China was wary that Annex II, which listed conflicts not before the Council, could push issues onto the body’s agenda through the “backdoor,” adding to an escalating list of agenda items. Russia and the UK were sensitive to the mention of Chechnya and Northern Ireland, respectively, in some of the Secretary-General’s reports on children and armed conflict. The United States, sceptical of a thematic approach, maintained that the Council should react to specific situations.

The views of elected members varied, depending on regional and national concerns. Some African countries, especially Benin, played an instrumental role in getting resolution 1612 adopted. Elected Latin American countries, Argentina and Brazil, were hesitant, influenced by Colombia, which objected to being mentioned in Annex II.

11.2. Current Dynamics

With time, members have become more comfortable with this issue and many seem proud of the achievements of the Working Group. Some positions have shifted or at least become flexible enough to allow for substantive developments. Some of this may be due to frequent regular working level contacts among the Group members creating a more positive environment which has filtered up to the Council. While differences remain, there now appears to be a genuine commitment to the issue of children and armed conflict.

The question of whether the child protection issues have an ongoing place on the Council’s agenda appears to be definitely resolved. Public statements of Council members in the last two open debates in 2006 showed almost universal support for the monitoring and reporting mechanism and for the Working Group.

France continues to be the key player and has established its mark on the Working Group in both style and substance. France’s commitment to this issue from the level of foreign minister down, has impressed Council members, who say that without France’s leadership it would be a very different picture.

The UK has now become openly supportive. Belgium and Italy have been strong proponents.

The US participates more actively in this issue. However, its delegates are cautious about the legal implications of the Working Group’s activities.

Russia supports the idea of giving equal weight to all six grave violations against children rather than just child soldiers as the criteria for including a party to a conflict in the annexes of the Secretary-General’s report. It is also keen for the Council to focus attention on the situation of children involved in other serious conflicts on its agenda, rather than primarily those in Africa.

China is supportive of the issue as a whole but continues to be hesitant to the idea of sanctions as a means of addressing the problem and is cautious about moving too quickly in expanding criteria used in the monitoring and reporting mechanism or expanding the mandate of the Working Group.

Some members of the Council feel, given the number of African situations under consideration, African Council members should play a more proactive role.

Some of the issues of the past are likely to emerge again now that the Working Group is fully operational. For a period of time in the interest of getting it going, members appear to have allowed concerns to simmer below the surface. It may be that the issue of whether to continue looking at situations not on the Council’s agenda will resurface. In this regard, it is not insignificant that China mentioned in the November 2006 open debate that there should be different approaches to dealing with situations that are on the Council’s agenda and those that are not.

The issues of expanding the criteria for the Secretary-General’s lists and expanding the monitoring and reporting mechanism are likely to be raised again. But many, even France, are cautious about tinkering too soon with structures that appear to be working reasonably well and want a period of further consolidation before expanding either the mechanism or the scope of the Working Group.

A number of members are reluctant to take stronger action, such as targeted sanctions against leaders responsible for particularly grave violations, or punishing those listed in annexes to the Secretary-General’s reports for years. The need to work by consensus has resulted in the lowest common denominator for some recommendations.

Members are also wary of overlapping priorities. For example, when the report on children and armed conflict in Myanmar was due to be considered at the end of 2007, China requested it be moved to a later date because of the Council’s frequent focus on events in Myanmar. China finally agreed to let the Working Group look at the report, but as of January 2008 no conclusions have emerged.

top

As the implementation of resolution 1612 moves toward the next phase, several options present themselves.

Options for the monitoring and reporting mechanism include:

- expanding the criteria so that the issue of child soldiers is not the only trigger for placing groups in the annexes of the Secretary-General’s report. Some members suggest sexual violence. Others want all six major violations against children to be used as the base criteria which could expand the list considerably; and

- making situations listed in Annex II (i.e. situations not on the Council’s agenda) automatically subject to the monitoring and reporting mechanism. Currently the relevant governments volunteer to participate.

Options for the Working Group and the reporting by the Secretary-General include:

- proposals for stronger measures such as a ban on arms exports and targeted financial and travel restrictions in the most egregious cases;

- a system to monitor responses to requested action and their implementation;

- more transparency regarding the action taken and the follow-up; and

- a clearer requirement for the Secretary-General to include in all reports a standard section on children and where relevant, comments and observations of the Working Group’s proposals.

Other options to more effectively carry out action suggested by the Working Group include:

- Expanding the mandate of the Working Group and requesting it to recommend individuals for targeted measures to the Council and oversee implementation of such measures when there is no appropriate sanctions committee.

- Requesting the Working Group to establish a more systematic process to ensure that its decisions are reflected in Council decisions on relevant country-specific issues.